|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Retina/Uveitis Quiz 24: A 60-year-old man with a progressive, bilateral, vision loss

|

Printer Friendly

|

Lily S. Ooi, MBBS

Lily S. Ooi, MBBS | Princess Alexandra Hospital Mark Donaldson, FRANZCO | Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia February 3, 2011

|

|

[Back to Questions] [Back to Retina/Uveitis]

|

Figure 1

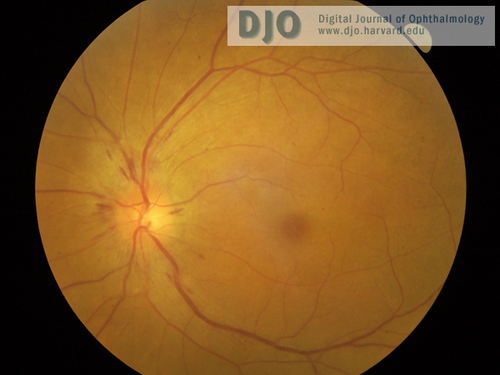

Left fundus showing disc swelling with nerve fiber layer hemorrhages.

|

Figure 2

Right fundus, with similar appearance to left fundus.

|

Figure 3

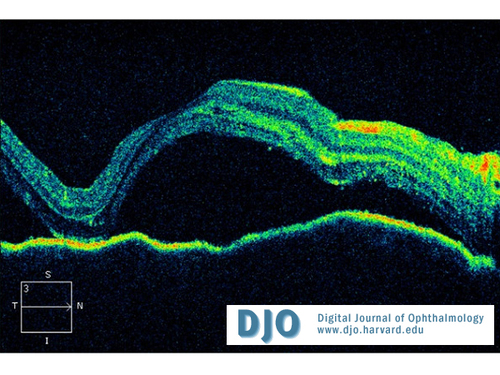

OCT of right macula (left macula has similar appearance).

|

Figure 4

Right macular one week after treatment.

|

| | Case History | | A 60-year-old Vietnamese man presented with a 2-week history of progressive bilateral vision loss associated with bilateral hearing loss. He had a history of well controlled diabetes and ischemic heart disease. There was no other relevant ocular history, and he was otherwise in good health. Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/60 in both eyes. Slit-lamp examination showed bilateral anterior uveitis, vitritis, disc swelling with nerve fiber layer hemorrhages (Figures 1 and 2), and multifocal subretinal exudative detachments (Figure 3). | | | Questions and Answers | 1. What is the differential diagnosis?

Answer: The differential diagnosis of bilateral panuveitis is infection; autoimmune disease; idiopathic, sympathetic ophthalmia; and masquerade syndrome such as lymphoma.

It is important to exclude infections, such as syphilis, tuberculosis (TB), and HIV. Autoimmune diseases that can present with this picture are sarcoidosis and Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome. Other autoimmune diseases to consider include systemic lupus erythematous and systemic vasculitis, such as Wegener’s granulomatosis, although this would not be a common presentation of either of these conditions.

Sympathetic ophthalmia can present as in this case; however, in the absence of a history of ocular trauma or surgery, this diagnosis is unlikely.

2. What further history or investigations are necessary to make the diagnosis?

Answer: Further history could exclude previous ocular trauma or surgery; symptoms of infections; meningeal signs, including headache, dizziness, tinnitus; or neurological disturbances.

Further investigations include the following:

• Blood workup, especially serology for syphilis, HIV, TB, and vasculitic screening, including antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody testing and serum angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE).

• Chest X-ray to exclude TB or lymphadenopathy.

• MRI/MRV to exclude any central nervous system (CNS) lesions.

• Lumbar puncture/cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis to exclude atypical meningitis and CNS lymphoma. CSF lymphocytic pleocytosis is common in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome.

• Optical coherence tomography (OCT) to detect multifocal exudative retinal detachments found in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome.

• Fundus fluorescein angiography to detect multifocal choroiditis found in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome.

All the investigations for this patient were normal except mild CSF lymphocytic pleocytosis. The CD4:CD8 ratio was normal, with no abnormal lymphocytic cells in the cytology analysis.

3. What is the most likely diagnosis?

Answer: In the absence of a history of ocular trauma, and any positive investigation findings, the most likely diagnosis is Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, especially considering the associated history of hearing loss. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome is a multisystem inflammatory disorder that involves the ocular, meningeal, auditory, and cutaneous systems. The exact etiology is unknown. It is diagnosed by excluding other inflammatory causes and by observing the presence of specific clinical entities. According to the revised diagnostic criteria by international workshop on Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, the criteria for the diagnosis are as follows (1):

I. No history of ocular trauma or surgery.

II. No clinical or laboratory evidence of other inflammatory causes.

III. Bilateral ocular involvement:

a. Early manifestations

i. Diffuse choroiditis (with or without anterior uveitis, vitritis, disc hyperemia)

ii. With equivocal fundus finding. Both of the following two must be present: fluorescein angiogram findings: delay in choroidal perfusion, multifocal pinpoint leakage, large placoid hyperfluorescence within subretinal fluid, or optic disc staining; and ultrasound findings: diffuse choroidal thickening without posterior scleritis.

b. Late manifestations

i. Previous history suggestive of early ocular manifestation of VKH, and either both (ii) and (iii) below, or multiple signs from (iii)

ii. Ocular depigmentation (sunset fundus or limbal depigmentation known also as sugiura sign)

iii. Other ocular signs: nummular retinal depigmentation, retinal pigment epithelial pigment clumping, or recurrent or chronic anterior uveitis.

IV. Central nervous system or auditory complaints: meningismus, tinnitus, or CSF pleocytosis.

V. Integumentary findings (not preceding the CNS or ocular manifestations): alopecia, poliosis, or vitiligo.

A diagnosis of complete VKH requires the presence of all 5 criteria. Incomplete VKH is made when only criteria I-III are present together with either IV or V. When only the first 3 criteria are present, the diagnosis is probable VKH.

4. What are the clinical features of this condition?

Answer: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome is more common in pigmented races such as Asian and Hispanics than whites. There is an association between human leukocyte antigens (HLA) and VKH patients from different ethnicities. HLA-DR4 and HLA-Dw53 are more common in Chinese patients,(2) HLA-DR1 and HLA DR4 more common in Hispanic patients,(3) and HLA DRB1 in Indian patients.(4)

Clinical manifestations typically follow four stages.(5) First, a prodromal stage, with fever, meningismus, tinnitus, hearing loss, or other neurological symptoms. This is followed usually 3 to 5 days later by the acute ocular manifestation stage, which can be uveitis, choroiditis, serous retinal detachment, disc swelling, or a combination of these. The convalescent stage follows with depigmentation of skin (poliosis, vitiligo) and uveal tissue (sunset glow fundus) months later. Eventually the recurrent, or chronic uveitic, stage follows, mainly characterized by anterior uveitis.

5. What is the treatment?

Answer: Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome responds well to systemic steroid treatment (1-2 mg/kg/day). Recurrence rates are high if steroid treatment is tapered too fast. Approximately 50% of these recurrences occur within the first 6 months of rapid tapering of the steroid. In refractory cases or if there is intolerance of steroids, other immunosuppressants (ie, cyclosporine, azathioprine), or cytotoxic agents (ie, cyclophosphamide) can be used. The emerging evidence suggests that combination therapy of corticosteroids and cyclosporine is more effective that corticosteroids alone.(6) Other alternative therapies, such as biologic agents (anti-TNF-apha, IFN-alpha and cytokine receptor antibodies), and anti-VEGF agents, have been reported in some studies to show promising results.(7)

The patient was treated with 1mg/kg/day of oral prednisolone with a rapid improvement of his vision. After 1 week, his visual acuity improved to 20/40 in the right eye and 20/30 in the left. Significant improvement of panuveitis and exudative retinal detachment as demonstrated in the OCT of the right macula (Figure 4).

He was discharged with slow taper of the oral steroids. Due to his history of diabetes, therapy with oral cyclosporine was initiated to allow for more rapid taper of systemic steroids over 3-4 months.

References

1. Read R, Holland G, Rao N, et al. Revised Diagnostic Criteria for Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Disease: Report of an International Committee on Nomenclature. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:647-52.

2. Moorthy R, Inomata H, Rao N. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome. Surv Ophthalmol 1995;39:265-92.

3. Weisz JM, Holland GN, Roer LN, et al. Association between Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome and HLA-DR1 and DR4 in Hispanic patients living in southern California. Ophthalmology 1995;102:1012-15.

4. Tiercy JM, Rathinam SR, Gex-Fabry M, et al. A shared HLA-DRB1 epitope in the DR beta first domain is associated with VKH syndrome in Indian patients. Molecular Vision 2010;16:353-8.

5. Nattaporn Tesavibul. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada Syndrome. MERSI Ocular Immunology and Uveitis Foundation / Medical professionals / articles. http://www.uveitis.org/medical/articles/case/VKH.html (accessed October 9, 2010).

6. Liu X, Yang X, et al. Inhibitory effect of cyclosporine A and corticosteroids on the production of IFN-gamma and IL17 by T cells in Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2009;131:333-42.

7. Bordaberry MF. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease: diagnosis and treatment update (review). Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 2010;21:430-5. | | | [Back to Questions] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Welcome, please sign in

Welcome, please sign in  Welcome, please sign in

Welcome, please sign in