|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

An 8-year-old with a unilateral droopy eyelid

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 2022

Volume 28, Number 1

February 4, 2022

|

Printer Friendly

Download PDF |

|

|

Maxwell G. Su, MD

Maxwell G. Su, MD | Baylor Scott & White Hospital, Temple, Texas Jana Waters, MD | Baylor Scott & White Hospital, Temple, Texas Matthew Recko, MD | Baylor Scott & White Hospital, Temple, Texas

|

|

|

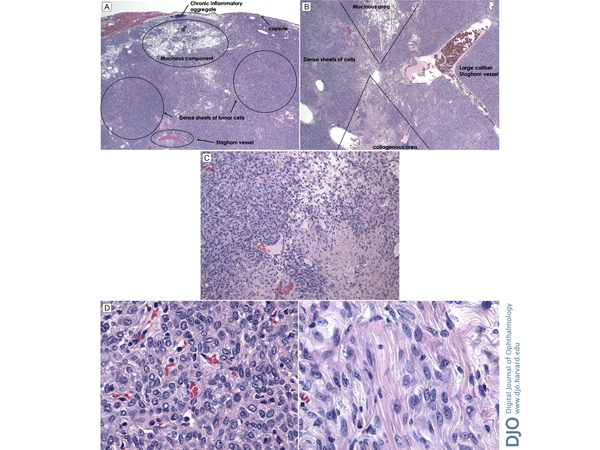

| Diagnosis and Discussion | Histopathologic examination showed an encapsulated tumor composed of dense sheets of spindled cells growing haphazardly; areas of myxoid change and inflammatory cell aggregates were also noted, as was a staghorn-type vascular pattern (Figure 5). Immunostains showed diffuse positivity of the spindle cells for CD34, BLC-2, and CD99; smooth muscle actin and CD31 highlighted intratumoral vasculature (Figure 6). S100, desmin, and keratin stains were negative. The resulting pathologic diagnosis was solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) of the orbit.

SFTs most often occur in the pleura, mediastinum, or lung, but extrapleural sites include the orbit. The tumor does not show any sex predilection;(1-4) SFTs usually present in older age groups, but a small number have been reported in pediatric patients. Tumor size can range from 0.4 to 10 cm, with a mean of 1.3–2.6 cm. They are round to ovoid, mobile, nontender, and are occasionally the cause of mechanical ptosis or diplopia.(4-6) Most SFTs follow a benign course; however, rare exceptions have been reported to be more aggressive, transforming into a malignant tumor with metastasis.(5,7)

On ultrasound, SFTs are firm and noncompressible, display low-to-medium internal reflectivity (tumors with densely packed cells typically are low reflective), and regular internal structure (SFTs typically have a homogeneous architecture, moderate sound attenuation, and possibly some degree of vascularity).(8,9) Computed tomography (CT) or MRI will reveal encapsulated, ovoid masses typically located in extraconal tissue and without bony erosion.(5,8) CT scan may reveal a moderately enhancing, high-density mass. T1-weighted MRI demonstrates hypointense to isointense signal with respect to gray matter, and depending on the density of the tumor, T2-weighted MRI may either reveal a hypointense or hyperintense clearly demarcated mass.(7,8)

Complete surgical resection with clear margins is necessary, because recurrence and malignant transformation, although rare, is possible.(5,7-12) Excision alone may suffice, but excision with chemotherapy and radiotherapy may be warranted.(12) Most patients with residual disease left after resection fare well; however, a case of malignant transformation leading to high-grade sarcoma 9 years after initial resection and relapse treated with methotrexate, corticosteroids, antibiotics, and radiotherapy has been reported.(11) It was observed that residual infiltrative margins may serve as a predisposing factor for relapse, and radiotherapy should be considered with caution. Thus, long-term follow-up is necessary for patients diagnosed with SFT.(3,7,11,12)

SFT typically affects adults, with a median age range of 24-72 years; however, orbital SFT has been reported in a 5-year-old patient, underscoring the fact that SFT in children should not be overlooked, because a missed diagnosis could prove devastating.(11)

SFTs often grow in a “patternless” fashion, with alternating areas of hypo- and hypercellularity, often with staghorn-type vasculature. They show strong positive immunoreactivity to CD34, CD99, bcl-2, and vimentin but negative reaction to S-100 protein and smooth muscle actin.(1-4,8) CD34, which is most consistently positive in SFTs, is a glycoprotein found on the surface of hematopoietic progenitor cells, blood vessel endothelium, the dendritic interstitial cells of mesenchyme, and certain connective tissue cells in the skin.(9,10)

SFT and hemangiopericytoma are considered the same entity, however, the former term is now preferred. SFT is translocation defined by the presence of the NAB2-STAT6 gene fusion, as detected with fluorescence in situ hybridization, next generation sequencing, or with a STAT6 immunohistochemical stain. Although our patient’s pathology is certainly consistent with solitary fibrous tumor, it would have been helpful to have one of these, because CD34, BCL2, and CD99 are found in but not specific for this tumor. Solitary fibrous tumors demonstrate CD34, Bcl-2, p53, and Ki-67 positivity, collagen-rich stroma, fibroblast-like cells, and giant cells.(6) Fibrous histiocytomas demonstrate different pathogenesis and immunostaining patterns, such as STAT6 and CD34 negativity. As stated previously, malignant transformation is rare; however, if present would appear as mitotic figures greater than 4 per 10 high-power fields with cellular pleomorphism, hypercellularity, nuclear atypia, high MIB-1 labelling, and focal areas of necrosis.(4,6,8,11)

Although exceptionally rare in the pediatric population, orbital solitary fibrous tumors should be considered in the differential diagnosis in patients presenting with painless orbital masses causing mechanical ptosis. SFTs can be visualized on ultrasonography, MRI, and CT imaging. Management includes complete resection with clear margins and proper identification requires immunohistochemical evaluation. Most cases of orbital SFTs are benign and with proper treatment patients typically have a very good prognosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Robert Rosa Jr. for performing gross specimen sectioning and immunohistochemical staining for the pathology slides. | |

|

Figure 5.

A, Overlying capsule surrounding areas of chronic inflammatory aggregate, mucinous components, dense sheets of collagen producing tumor cells, and stag horn vessels in a “patternless” arrangement. B, Histologic slide displaying collagenous area, large-caliber stag horn vessel, dense sheet of tumor cells, and mucinous area. C, Higher-power image displaying dense sheet of tumor cells, mucinous area, and collagenous area. D, Dense sheet of spindle-shaped cells with numerous vascular slits (left) and tumor cells producing collagen fibrils (right).

|

|

|

Figure 6.

Tumor cells were diffusely and strongly positive for CD34 (A) and negative for CD31 (B); there was positive CD31 staining from the endothelial cells of the blood vessels. Tumor cells were strongly positive for vimentin (C) and negative for smooth muscle actin (D). The smooth muscle in the blood vessel walls stained positive for smooth muscle actin. Tumor cells were diffusely positive for cytoplasmic staining of BCL-2 (E) and for cytoplasmic staining of CD99 (F).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Welcome, please sign in

Welcome, please sign in  Welcome, please sign in

Welcome, please sign in