34 year old man presents with transient loss of vision in his right eye

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 2005

Volume 11, Number 13

July 10, 2005

Volume 11, Number 13

July 10, 2005

Past Medical History:

- unremarkable

Past Ocular History:

- unremarkable

Medications:

- multivitamin a day

Habits:

- no smoking

- social beer and wine

Family History:

-no significant history of blindness

VA 16/15 16/13

Color 10/10 10/10

Amsler Grid full full

Humphrey VF full full

Exophthalmometry 14 mm 14 mm

Orbits no resistance to retropulsion, no masses palpated

Pupils brisk, no APD brisk, no APD

EOM full full

IOP 16 mmHg 17 mmHg

Anterior Segmentunremarkable unremarkable

Lens clear clear

Dilated Exam5-6 cells/hpf 3-4 cells/hpf

Color Photo OD

Color Photo OS

Serum

- Sedimentation Rate – 25 (normal range 0-15)

- ACE – 71 (normal range 8-52)

- Lysozyme – 19 (normal range 9-17)

- Lyme disease titer – positive

- Western Blot – negative

- FTA-ABS – reactive – 3+

- RPR – reactive – 1:512 titer

- TPPA – reactive

Lumbar Puncture

- Normal opening pressure

- Clear, colorless

- Wbc, glucose and total protein normal

- No growth on culture

- VDRL – negative

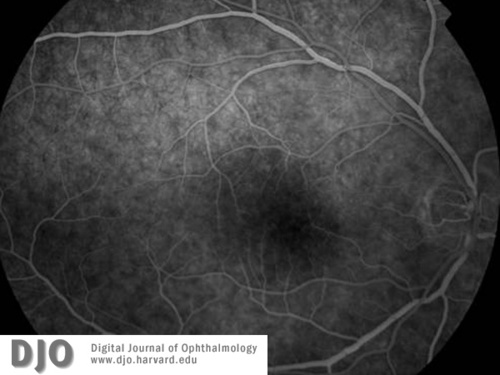

IVFA Early

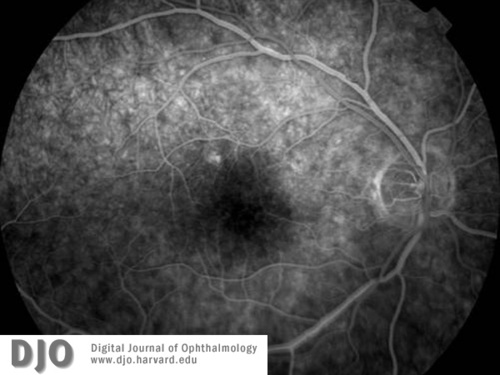

IVFA Early 2

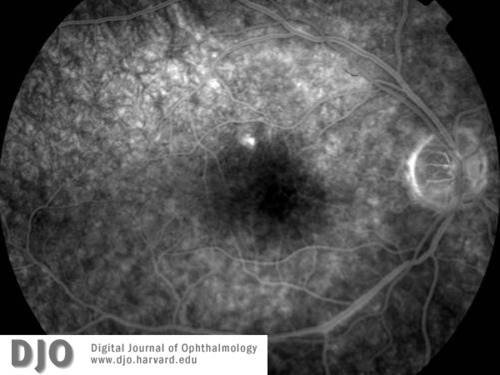

IVFA Mid Phase

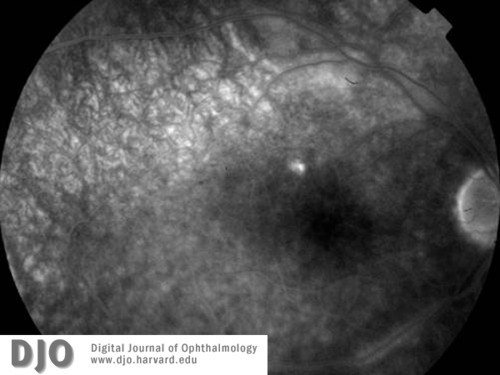

IVFA Late

Note the vasculitis along the inferior arcade.

Note the vasculitis along the inferior arcade.

- Syphilis

- Tuberculosis

- Lyme disease

- Amyloidosis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus

- Lymphoma

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted, chronic, systemic infection caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. If left untreated, the disease progresses through four stages, with the potential to case significant morbidity to any major organ of the body. T. pallidum rapidly penetrates intact mucous membranes or small abrasions in skin and within hours enters the lymphatics and blood to produce a systemic infection long in advance of the appearance of a primary lesion. The first stage, primary syphilis, follows an incubation period of 10 to 90 days, after which patients typically develop a non-tender, indurated, non-purulent chancre at the site of inoculation. The chancres are filled with spirochetes and usually resolve spontaneously without therapy approximately 4 weeks after their appearance. In as many as 60% of patients with syphilis, the primary chancre goes unnoticed.

Four to 10 weeks following the appearance of the chancre, nearly all untreated patients develop secondary syphilis. This stage signifies hematogenous dissemination of the spirochetes which can lead to neurologic, ophthalmologic, gastrointestional, and hepatic disease. The eyes are affected in approximately 10% of cases. A diffuse maculopapular rash, often most prominent on the palms and soles, is the presenting complaint in more than 70% of patients with secondary syphilis. Other symptoms can include fever, generalized non-tender lymphadenopathy, headache, malaise, anorexia, nausea, joint pain, mouth ulcer, and hair loss. Similar to the primary stage, these symptoms resolve spontaneously without treatment. However, up to a quarter of untreated patients may develop recurrences, most frequently in the first year.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines latent syphilis as the asymptomatic period from the disappearance of the secondary manifestations until therapeutic cure or the development of tertiary syphilis. The latent stage can last from months to a lifetime. This stage is divided into early latent, with relapse up to 1 year after initial infection, and late latent, with relapse after 1 year. Approximately one-third of untreated patients progress to tertiary syphilis.

Tertiary syphilis represents, at least in part, an obliterative endarteritis that can affect nearly any organ in the body. It can be divided into a more benign localized granulomatous reaction, the gumma, and a severe diffuse inflammation involving primarily the cardiovascular and central nervous systems. Gummas, most frequently found in the skin and mucous membranes, can involve any part of the body, including the choroid and iris. Cardiovascular syphilis consists of aortitis, aortic aneurysms, aortic valve insufficiency, and narrowing of the coronary ostia. Neurologic involvement includes meningeal, meningovascular, and parenchymatous (tabes dorsalis and general paresis) syphilis. Cardiovascular and neurologic involvement in tertiary syphilis carries serious risks of morbidity and mortality.

Central nervous system (CNS) involvement of syphilis has inaccurately been considered a late manifestation of the disease. As cerebral spinal fluid studies demonstrate, T. pallidum invades the CNS early in the disease; however, only approximately 5% of patients will become symptomatic from this early invasion. After the initial invasion, untreated or inadequately treated infection may resolve spontaneously, develop into asymptomatic meningitis, or become acute syphilitic meningitis. This early neurosyphilis can occur within weeks to years after the primary infection, and may coexist with primary and secondary syphilis. The blood vessels and meninges are more often affected than the brain or spinal cord parenchyma. Late neurosyphilis, rare in the age of antibiotics and public health surveillance, occurs decades after primary infection, and predominantly affects the brain and spinal cord parenchyma to produce general paresis and tabes dorsalis.

The ocular manifestations of syphilis are protean and can occur at any stage of the disease. Numerous authors have illustrated the ability of syphilis to mimic different ocular disorders, leading to misdiagnoses and a delay in the administration of appropriate antimicrobial therapy. The most common presentation of syphilis in the eye is uveitis. Other frequent syphilitic ocular manifestations, which can occur at any stage of the disease, include interstitial keratitis, anterior, intermediate, and posterior uveitis, chorioretinitis, retinitis, retinal vasculitis and cranial nerve and optic neuropathies.

Diagnosis is centered around a high level of clinical suspicion and includes non-treponemal tests, such as the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) and Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR), and treponemal specific tests, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed (FTA-ABS) and T. pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA). Patients suspected of having syphilis are initially tested using one of the nontreponemal tests (VDRL or RPR), with the treponemal tests (FTA-ABS or TP-PA) used to confirm a positive result. There is no universally established criteria for the diagnosis of neurosyphilis. The diagnosis depends on various combinations of reactive serum serologic tests, abnormalities in CSF cell count and protein level, and a reactive CSF VDRL, all coupled with the clinical assessment. A positive CSF VDRL is considered diagnostic for neurosyphilis; however, it may be nonreactive in some cases of active neurosyphilis. Sequential CSF leukocyte counts and CSF antibody titers are used to gage the effectiveness of therapy.

All patients with newly diagnosed syphilis should be tested for co-infection with human immunodeficiency virus, as the risk factors are similar for both diseases. Additionally, all patients with ocular syphilis should be tested for neurosyphilis.

Parenterally administered Penicillin G is the preferred drug for treatment of all stages of syphilis. The preparation, dose, route of administration, and duration of therapy are determined by the stage and the clinical manifestations of the disease. Sexual partners of patients with syphilis should also be evaluated clinically and serologically and treated accordingly. With proper diagnosis and prompt antibiotic treatment, the majority of cases of syphilis can result in a cure. If unrecognized, or treated inappropriately, in one third of patients, the disease will progress to tertiary syphilis and can result in significant morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular and neurological complications.

Singh AE, Romanowski B. Syphilis: review with emphasis on clinical, epidemiologic, and some biologic features. Clin Microbiol Rev 1999;12(2):187-209.

Anderson J, Mindel A, Tovey SJ, Williams P. Primary and secondary syphilis, 20 years' experience. 3: Diagnosis, treatment, and follow up. Genitourin Med 1989;65(4):239-43.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Surveillance 2003. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, September 2004.

Goldmeier D, Guallar C. Syphilis: an update. Clin Med 2003;3(3):209-11.

Margo CE, Hamed LM. Ocular syphilis. Surv Ophthalmol 1992;37(3):203-20.

Durnian JM, Naylor G, Saeed AM. Ocular syphilis: the return of an old acquaintance. Eye 2004;18(4):440-2.

Aldave AJ, King JA, Cunningham ET, Jr. Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2001;12(6):433-41.

Deschenes J, Seamone CD, Baines MG. Acquired ocular syphilis: diagnosis and treatment. Ann Ophthalmol 1992;24(4):134-8.

Hook EW, 3rd, Marra CM. Acquired syphilis in adults. N Engl J Med 1992;326(16):1060-9.

Villanueva AV, Sahouri MJ, Ormerod LD, Puklin JE, Reyes MP. Posterior uveitis in patients with positive serology for syphilis. Clin Infect Dis 2000;30(3):479-85.

Savir H, Kurz O. Fluorescein angiography in syphilitic retinal vasculitis. Ann Ophthalmol 1976;8(6):713-6.

Yokoi M, Kase M. Retinal vasculitis due to secondary syphilis. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2004;48(1):65-7.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines 2002. MMWR 2002;51 (No. RR-6).

Larsen SA, Steiner BM, Rudolph AH. Laboratory diagnosis and interpretation of tests for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev 1995;8(1):1-21.