An 86 year old woman with headache and limited eye movements

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 2005

Volume 11, Number 10

April 12, 2005

Volume 11, Number 10

April 12, 2005

Bilateral cavernous carotid aneurysyms

Video clip of eye movements demonstrating reduction in abduction, adduction, upgaze and downgaze in both eyes

Video clip of eye movements demonstrating reduction in abduction, adduction, upgaze and downgaze in both eyes

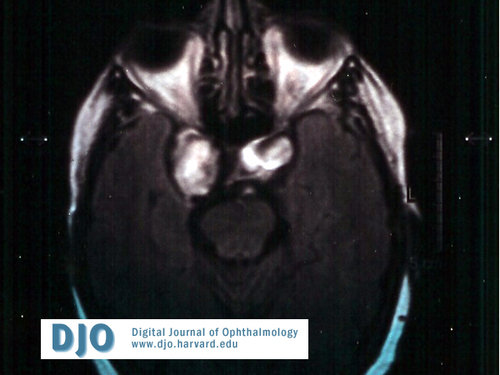

Axial T1 weighted MRI

MRI demonstrating bilateral carotid aneursyms within the cavernous sinus

MRI demonstrating bilateral carotid aneursyms within the cavernous sinus

Myasthenia gravis

Chronic progressive external ophthalmolplegia

Neoplastic infiltration

Space occupying lesion within the cavernous sinus

Intracavernous carotid aneurysms occur predominantly in women over the age of 50, and behave differently from other intracranial aneurysms as they rarely hemorrhage into the subarachnoid space because of their extradural location. If the aneurysm ruptures, carotico- cavernous fistula is the most likely outcome, producing symptoms of complete ophthalmoplegia, proptosis, conjunctival chemosis, orbital congestion, optic neuropathy, optic disc oedema, and retinal haemorrhages.

Intracavernous carotid aneurysms may slowly enlarge without rupture or producing symptoms. The commonest neuro-ophthalmic manifestation is diplopia, due to compression of one or more of the oculomotor nerves. The Abducens nerve is commonly affected as it lies within the cavernous sinus, adjacent and lateral to the carotid artery. The Oculomotor nerve lies superiorly within the dura mater that forms the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. Movement of the Oculomotor nerve is restricted when compressed, as the petroclinoid and interclinoid ligaments tether the nerve, producing symptoms of superior, medial, inferior and inferior oblique paresis. Trochlear nerve paresis as an isolated finding is rare. When an Oculomotor palsy is already present, the function of superior oblique can be demonstrated clinically by eliciting incyclotorsion on attempted down gaze, in our case this appeared to be present bilaterally, and may be explained by the relative laxity in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus at this point, sparing the Trochlear nerve.

Aneursymal growth may be so mild or slow growing that, patients present without diplopia but signs of oculomotor synkinesis such as pseudo-Graefe’s sign, miosis on attempted adduction and light near dissociation of the pupils.

Facial pain may also be a presenting complaint, as the ophthalmic and maxillary divisions of the Trigeminal nerve are located in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. Trigeminal sensory loss is rarely elicited on examination. The combination of pain in the distribution of the ophthalmic division of the Trigeminal nerve and a post ganglionic Horner’s syndrome (due to the relationship of the sympathetic plexus to the internal carotid artery) is referred to as Raeder’s syndrome. Rarely carotid cavernous aneurysms can compress the pituitary gland medial to the cavernous sinus producing symptoms of headache, amenorrhea, decreased libido, hypothyroidism, or diabetes insipidus.

The treatment goal is to occlude the aneurysm before rupture, and minimize medical and neurological complications. Due to the inaccessible position of the intracavernous carotid aneurysm, direct surgical clipping may be difficult, and associated with over 3% mortatility and 7% morbidity. Those patients over 70 years have an increased risk due to increased medical complications and more friable vessels. In these situations a GDC (Gugliemi Detachable Coil) may be safer. The GDC coil is placed into the neck of the aneurysm percutaneously through a micro catheter. The soft platinum coil is packed into the neck and sac of the aneurysm until the aneurysm is separated from the circulation, a small electric current then allows separation of the coil from the steel guide wire. The morbidity and mortality after GDC embolisation varies from 3 to 6%. The main complications are embolism and Aneursymal rupture. Aneurysm occlusion rates are related to size, position and the neck of the aneurysm. Those aneurysms less than 10 millimetres diameter have a 75% chance of complete occlusion but for those over 10 millimetres the success falls to 40%. Long-term recurrence rate is between 5 and 10 %. In our case the patient decided not to proceed with intervention due to her age and the fusiform character of the aneurysms.

Bilateral carotid cavernous aneurysms have previously been described, occasionally mimicking other conditions. Bilateral ophthalmoplegia caused by bilateral cavernous carotid aneurysms are rare but should be included in the differential diagnosis.

1.Seltzer J,Hurteau EF. Bilateral symmetrical aneurysms of the internal carotid artery within the cavernous sinus;case report. J. Neurosurg. 1957 Jul.;14(4):448-51

2.Atri A,Sheen V. Cavernous sinus syndrome and headache due to bilateral carotid artery aneurysms. Arch Neurol. 2003 Sep;60(9):1327-8.

3.Matsumoto K,Kato A, Fujii K, Fujinaka T, Fukuhara R. Bilateral giant intracavernous carotid aneurysms mimicking a cavernous sinus neoplasm- case report. Neurol Med Chir( Tokyo) 1996 Aug;36(8):583-5.

4 Mindel JS,Charney JZ. .Bilateral intracavernous carotid aneurysms presenting as pseudo-ocular myasthenia gravis. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1989;87:445-57

5. Mindel JS,Sachdev VP. Bilateral intracavernous carotid aneurysms mimicking a prolactin secreting pituitary tumor. Surg Neurol. 1983 Feb;19(2):163-167

6.Locksley HB. Natural history of subarachnoid haemorrhage;intracranial aneurysm and arteriovenous malformation. J. Neurosurg. 1966;25:219-239.

7. Kupersmith MJ,Berenstein A,Choi IS. Percutaneous transvascular treatment of giant intracavernous aneurysms. Neurol. 1984;34:328-335.

8.Linkskey ME,Seckhar LN, Hersh W Jnr. Aneurysms of the intracavernous carotid artery.Clinical presentation,radiographic features and pathogenesis.Neurosurg. 1990;26:71-79