A 59 year old woman with acute visual field loss

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 2004

Volume 10, Number 9

September 15, 2004

Volume 10, Number 9

September 15, 2004

Ocular history:

- Nil

Medical history:

- Migraine for 15 years, always on left side.

- Hysterectomy six years ago

- Idiopathic pleural effusion eight months ago.

- 4 kg of weight gain for several months

Medications:

- Hormone replacement therapy patches

- Sumatriptan 50mgm tablets for migraine.

Family history:

- Father died of ischaemic heart disease 11years ago

Allergies:

-Nil

Social:

- Ex-smoker

Colour plates: 17/17 OD, 0/17 OS

Confrontational visual fields: Full OD. Superotemporal visual field defect respecting vertical meridian OS

Pupils: Dense RAPD OS

Motility: Full OU

Slit lamp examination: Anterior segments normal OU

Tonometry: 16 OD 18 OS

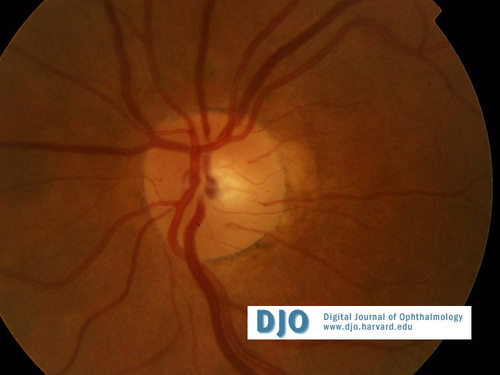

Fundi: Normal (figures 1 and 2)

Figure 1

Fundus OD at presentation.

Fundus OD at presentation.

Figure 2

Fundus OS at presentation.

Fundus OS at presentation.

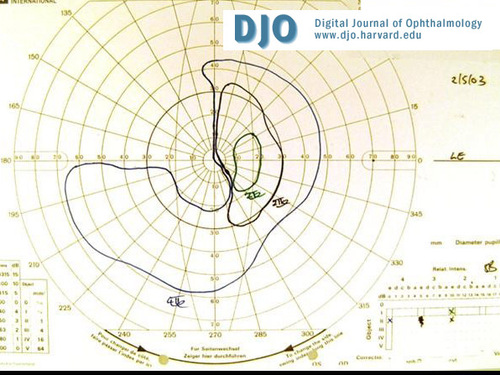

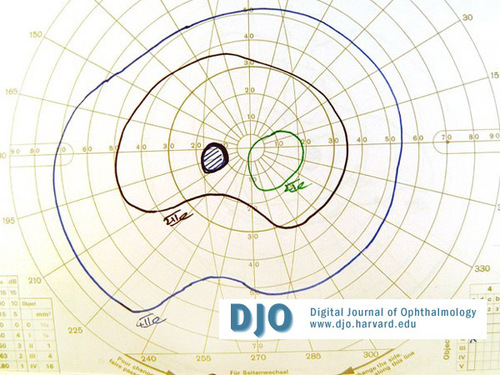

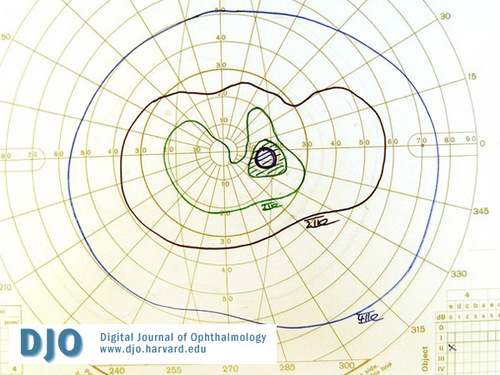

Figure 3

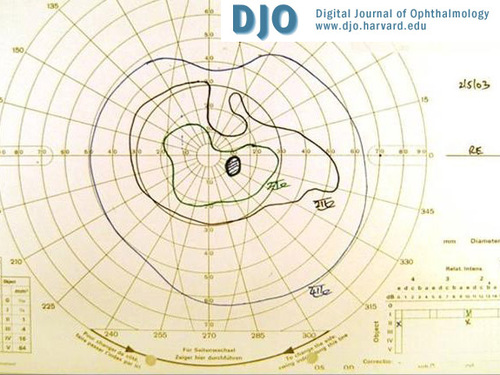

Visual field OS and OD (Figure 4) at presentation demonstrating a left junctional scotoma characterized by an ipsilateral central scotoma and a contralateral superotemporal field defect.

Visual field OS and OD (Figure 4) at presentation demonstrating a left junctional scotoma characterized by an ipsilateral central scotoma and a contralateral superotemporal field defect.

Figure 4

Visual field OD at presentation.

Visual field OD at presentation.

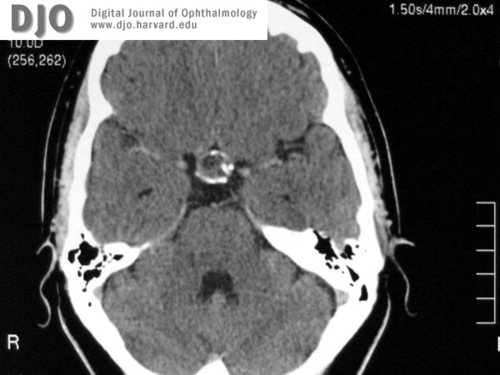

CT of the brain (figures 5 and 6) demonstated a suprasellar lesion showing calcification and cystic areas.

Figure 5

CT of the brain.

CT of the brain.

Figure 6

CT of the brain.

CT of the brain.

Differential diagnosis of chiasmal syndrome is a sellar (supra and parasellar) lesion, including

- Neoplastic: Pituitary tumour, glioma, craniopharyngioma, meningioma, chordoma

- Vascular: suprasellar carotid artery aneurysm, cavernous haemangioma

- Infection or inflammation: sarcoidosis, syphilis, tuberculosis, histiocytosis X

- Congenital cysts: arachnoid cyst, Rathke cleft cyst.

Radiological differential would include:

- Craniopharyngioma

- Calcified Aneurysm

- Meningioma

- Chordomas

- Astrocytoma

- Ependymoma

- Arachnoid cyst

Craniopharyngioma is rare, and accounts for 1-3% of intracranial tumours (5-10% in children) and 13% of suprasellar tumours (56% in children). There is slight male preponderance and no genetic relationship has been found. There is a bimodal peak, the largest peak being at the age of 5-14 years and a much smaller second peak at 50-70 years of age. The overall global incidence is 0.5-2 per 100,000 per year (1).

Craniopharyngioma is a slow-growing, ectodermal tumour arising from squamous cell rests derived from primitive buccal epithelium (Rathke's pouch) and occurring mainly on the infundibulum between the inferior surface of the brain and superior surface of the pituitary . Embryogenetic and metaplastic theories have been put forward to explain bimodal peak (2).

Macroscopically the tumour my be cystic, solid or, often, a mixture, and there is often focal calcification (produced by chronic reaction to leaking cyst contents). The cysts contain glittering, turbid, brownish-yellow fluid that is said to resemble machine oil.

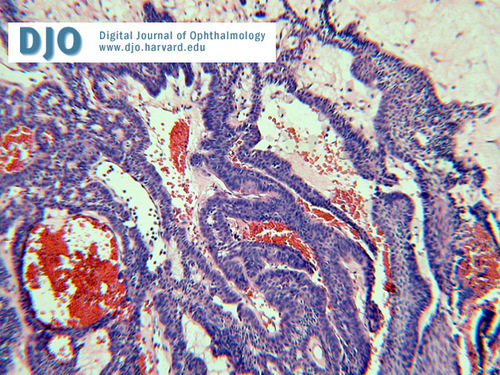

Microscopically it is composed of broad strands and cords of a multi- stratified squamous epithelium, most commonly of the adamantinomatous type with peripheral palisading as seen in figure 7. Compact nodules of "wet" keratin and dystrophic calcification are commonly seen. The papillary variant lacks the palisading and wet keratin formation.

Initial clinical manifestations of this tumour depend on the precise site of origin, the direction of the growth and the age of the patient. Three major clinical syndromes have been described relating to the anatomic relation of the craniopharyngioma with surrounding structures. Prechiasmal localization typically results in visual disturbances (37-68%). Retrochiasmal extension affects hypothalamus and commonly results in hydrocephalus and mental status abnormality (37-68%). Intrasellar craniopharyngioma usually manifests with headache (55-86%) and endocrinopathy (66-90%). Children are remarkably resistant to visual failure (2,3).

Ophthalmologists are often the first port of consultation and patients may present with headache, unilateral or bilateral visual loss, visual field loss, hemislide phenomenon, post fixational blindness, see-saw nystagmus, cranial nerve palsy, papilledema, and bow tie optic atrophy. Besides causing the chiasmal syndrome most commonly, craniopharyngioma has infrequently been reported to cause junctional scotoma, paracentral bitemporal hemianopia(anterior or posterior optic chiasma syndrome) or homonymous hemianopia (optic tract syndrome). However because of the suprachiasmatic location of the tumour there is a clear association between inferior visual field defects and craniopharyngioma, but in clinical practice most patients do not present with inferior field loss (as in our patient) (4). Pleomorphism- distinct change from one type of field defect into another type of visual field defect- is characteristic of craniopharyngioma. It is related to intermittent emptying of cyst fluid into ventricular system, a feature also responsible for fluctuating visual symptoms and masquerading acute disease processes like optic neuritis, infection or rapidly enlarging aneurysm (5).

Diagnostic studies include neuroimaging, endocrinologic and neuropsychologic work up. CT scan is the most sensitive and defines both calcified and cystic parts. MRI is important to plan surgical approach. Inspite the history of cold intolerance and weight gain, all endocrine workup in our patient was normal.

Craniopharyngiomas are histologically benign, but exhibit clinically malignant behaviour because of their proximity to important intracranial structures and their tendency to recur after what was thought to be total resection. There is yet no consensus on various treatment modalities. The options are total resection or subtotal resection with radiotherapy supported by hormonal replacement therapy. Other less tried treatment options are intracystic bleomycin, external beam radiation, and sterotactic radiation. Our patient underwent craniotomy and gross total resection with radiotherapy. Six months following her surgery her bilteral visual acquities were 6/5 and her postoperative fields had significantly improved. (figures 8 and 9).

Figure 7

Micrograph of the pathology specimen.

Micrograph of the pathology specimen.

Figure 8

Post-operative visual field OS.

Post-operative visual field OS.

Figure 9

Post-operative visual field OD.

Post-operative visual field OD.

2 Russell and Rubinstein. Pathology of tumours of the Nervous system,6th edition 1998.pages 629-640.

3 Crane TB, Yee RD, Helper RS, Hallinan JM. Clinical manifestations and radiologic findings in craniopharyngioma in adults. Am J Ophthalmol 1982;94(2):220-228.

4 Freitag SK, Miller NR. Visual loss in a 42- year-old man. Surv Ophthalmol 2000 May- Jun;44(6): 507-12.

5 Kennedy HB, Smith RJ. Eye signs in craniopharyngioma. Br J Ophthal 1975; 59(12):689-95.