A 54 year old woman with a red eye

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 2004

Volume 10, Number 8

July 28, 2004

Volume 10, Number 8

July 28, 2004

Initially she had not noticed any other visual or ocular symptoms but lately she felt that the vision was getting progressively worse in her right eye. She also reported intermittent diplopia especially in lateral and upgaze.

There was no significant past medical or surgical history except for mild hypertention which was well controlled on medication.

She was seen 5 days later at which time she had reduced vision in the right eye (6/24) and depressed color vision as tested using Ishiharas charts. The acuity and color vision were normal in the fellow eye.

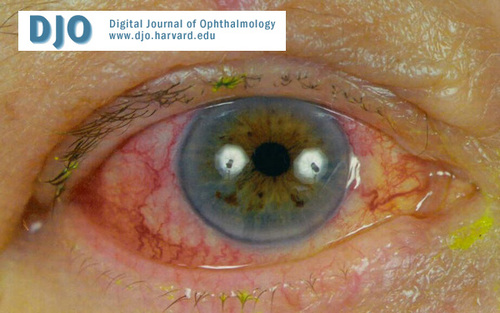

The right eye was injected and chemosed with prominent scleral vessels and associated lid edema (Figure 2). She also had axial proptosis measuring 5-6 mm and a right afferent pupillary defect. Motility of the right eye was limited in all directions (figure 3). The right anterior chamber appeared considerably shallower as compared to the left and the pressure had increased to 26 mm Hg (from a previously recorded value of 12).

The fundi appeared normal except for some dilated congested vessels on the right.

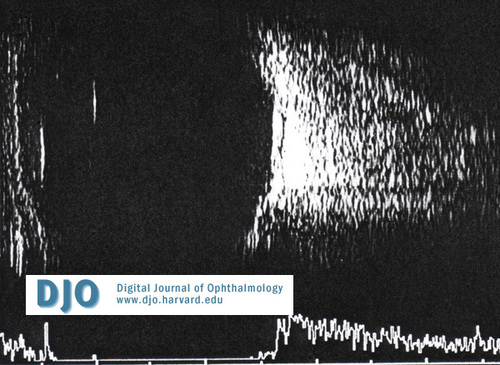

Figure 1

B scan ultrasound.

B scan ultrasound.

Figure 2

Appearance of the eye at presentation.

Appearance of the eye at presentation.

Figure 3

Photograph demostrating restricted motility OD.

Photograph demostrating restricted motility OD.

She was booked for an urgent CT scan, which was performed the same day.

The scan showed enlarged muscles in the right eye but more significantly a very large right superior ophthalmic vein (Figure 4). Further history obtained at this stage revealed an episode of bifrontal headache and eye pain 4 months prior.

She was referred urgently to the neurosurgeons with a working diagnosis of a caroticocavernous fistula. Cerebral angiography confirmed the diagnosis by demonstrating a fistula fed by the meningio-hypophyseal branch of the left internal carotis artery and a branch from the left external carotid artery. Drainage appeard to be via the superior ophthalmic vein which appeared thrombosed.

Figure 4

CT scan demonstrating enlargement of the right superior ophthalmic vein.

CT scan demonstrating enlargement of the right superior ophthalmic vein.

Thyroid eye disease

Carotico Cavernous fistula

Idiopathic Orbital Inflamatory Disease

Orbital malignancy

The fistula is usually initiated by a rent in the wall of the intracavernous internal carotid artery or its branches with short-circuiting of arterial blood into the venous complex of the cavernous sinus. This leads to raised venous pressure and reduced arterial perfusion with soft tissue swelling and anterior segment ischemia.

Fistulae may be asymptomatic or have a range of presentations including lid swelling, orbital pain, pulsating exophthalmos of varying degrees, subjective or ocular or cephalic bruit, diplopia, engorged conjunctiva and raised IOP. The fundal changes include dilated veins, disc edema, retinal hemorrhages, venous stasis retinopathy or even venous occlusions (1).

Enlarged extra ocular muscles are visible by ultrasonography as is reverse flow of blood in the superior ophthalmic vein (2). An aid to definitive diagnosis is complete angiographic evaluation with selective opacification of bilateral internal and external carotid arteries and vertebral circulation. Prominence of the superior ophthalmic vein is frequently detected on CT scan and MRI may help visualize lateral bulging of the cavernous sinus (3,4).

Therapy is directed towards relieving ocular symptoms and preserving vision. Many fistulae close spontaneously and do not require anything beyond intervention. However, sight threatening fistulae need more agressive treatment with the goal being thrombosis of the fistula with normalization of orbital hemodynamics. The preferred method of treatment is intravascular closure of the fistula, which may be achieved by detachable balloon micro catheterization techniques or embolization with Isobutyl –2-cyanoacrylate or polyvinyl alcohol particles

Another method of transvenous embolization utilizes Guglielmi detachable coils and fibered platinum coils. Various routes have been tried including inferior petrosal sinus (IPS) alone, IPS and inter-cavernous sinus, IPS and clival plexus, superior ophthalmic vein (SOV) via facial vein and SOV via superficial temporal vein (5).

Transvenous embolization through retrograde catheterization of the superior ophthalmic vein can allow complete coil occlusion of the lesion with marked improvements in visual outcome (6).

This case illustrates the spectrum of subtle to conspicuous ocular manifestations that can be seen in patients with CCF and its potential to present as an emergency. CCF should be included in the differential diagnosis of an "atypical" red eye. Recognition of arterialised conjunctival vessels and auscultation of an orbital bruit raises the possibility of a CCF, requiring prompt diagnostic studies (7).

1. Neuro-ophthalmlogy, Third edition, Joel S Glaser, Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Chapter 17, Pgs 605-611

2. Atta HR,Dick AD,Hamed LM et al: Venous stasis orbitopathy: A clinical and echographic study.Br J Ophthalmol 80:129. 1996)

3. Elster AD,Chen MYM,Richardson DM et al:Dilated intracavernous sinuses:an MR sign of carotid-cavernous and carotid-dural fistulas.AJNR Am J Neroradol 12:641,191

4. Anderson K, Collie DA,Capewell A.CT angiographic appearances of carotico-cavernous fistula.Clin Radiol 2001; 56, 514-6

5. Cheng KM, Chan CM, Cheung YL. Transvenous embolisation of dural carotid-cavernous fistulas by multiple venous routes: a series of 27 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003 Jan;145(1):17-29

6. Albuquerque FC, Heinz GW, McDougall CG.Reversal of blindness after transvenous embolization of a carotid-cavernous fistula: case report. Neurosurgery. 2003 Jan;52(1):233-6; discussion 236-7.

7. Bhatti MT, Peters KR. A red eye and then a really red eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2003 Mar-Apr;48(2):224-9.