27-year-old immuno-compromised male with presumed unilateral subretinal abscess and exudative retinal detachment

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 2003

Volume 9, Number 1

March 21, 2003

Volume 9, Number 1

March 21, 2003

Past ocular history: Non-contributory.

Past medical history: He was diagnosed two weeks previously with Cushing’s syndrome during an evaluation of weight gain and skin discoloration over the abdomen that revealed severe hypertension and renal failure requiring hemodyalysis.

Pupils: Equal, round, RAPD OS.

Motility: Full OU.

IOP:15 mmHg OD, 16 mmHg OS.

Slit-lamp exam: +1 anterior chamber cells and mild to moderate vitritis OS.

Fundus exam: OD: Normal; OS: 5-disk diameter subretinal mass at the posterior pole and exudative inferior-temporal detachment in OS.

Figure 1: Brain MRI:T2 weighted axial image shows a hyperintense lesion in the right posterior temporal region with edema (arrows)

Figure 2A: Precontrast T1 weighted axial image shows a lesion of mild hyperintensity with surrounding hypointense edema in the right posterior temporal region (arrow)

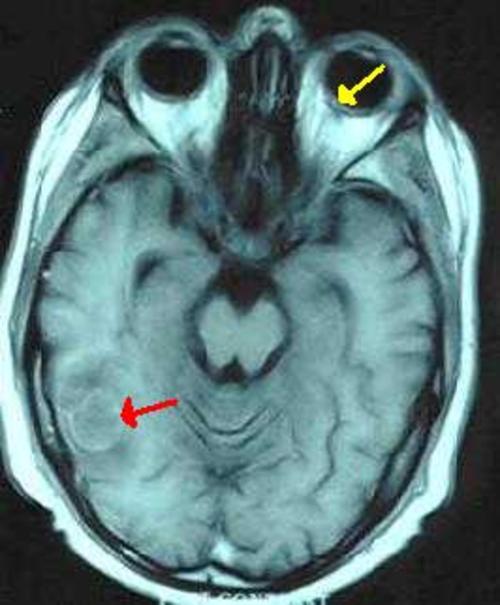

Figure 2B: Corresponding postcontrast T1 weighted axial image demonstrates rim enhancement of the lesion (red arrow). Also note the mild posterior enhancement in the left globe representing the enhancing retina (yellow arrow)

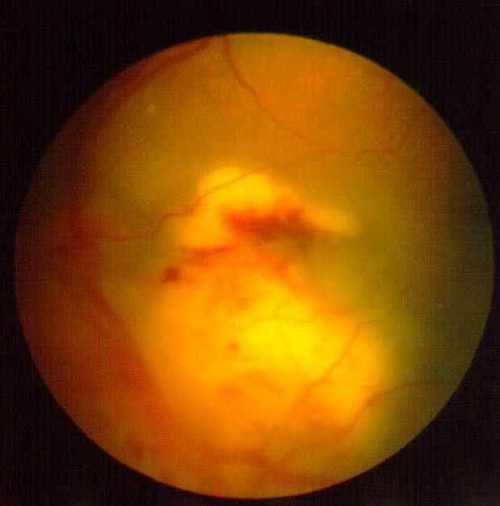

Figure 3A: Fundus photo of the left eye: Depicting subretinal mass at the posterior pole on the initial eye examination.

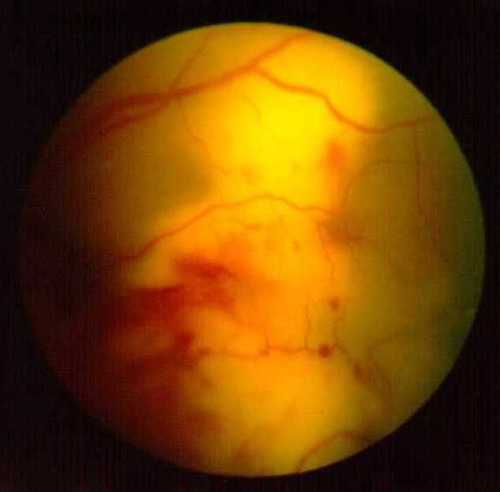

Figure 3B: Fundus photo of the left eye: Showing the marked increase in size of the subretinal mass 5 days later.

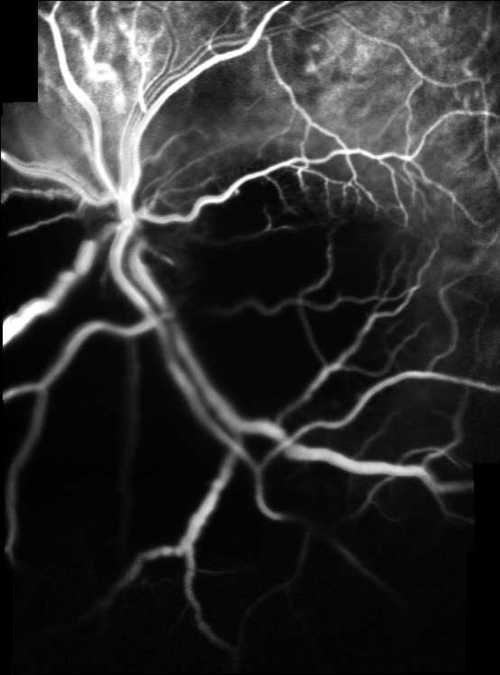

Figure 4A: Early phase of indocyanine green angiography composite picture obtained by Heidelberg SLO

Figure 4B: Early venous phase of fluorescein angiography composite picture obtained by Heidelberg SLO

Figure 1

Brain MRI:T2 weighted axial image shows a hyperintense lesion in the right posterior temporal region with edema (arrows)

Brain MRI:T2 weighted axial image shows a hyperintense lesion in the right posterior temporal region with edema (arrows)

Figure 2A

Precontrast T1 weighted axial image shows a lesion of mild hyperintensity with surrounding hypointense edema in the right posterior temporal region (arrow)

Precontrast T1 weighted axial image shows a lesion of mild hyperintensity with surrounding hypointense edema in the right posterior temporal region (arrow)

Figure 2B

Corresponding postcontrast T1 weighted axial image demonstrates rim enhancement of the lesion (red arrow). Also note the mild posterior enhancement in the left globe representing the enhancing retina (yellow arrow)

Corresponding postcontrast T1 weighted axial image demonstrates rim enhancement of the lesion (red arrow). Also note the mild posterior enhancement in the left globe representing the enhancing retina (yellow arrow)

Figure 3A

Fundus photo of the left eye depicting subretinal mass at the posterior pole on the initial eye examination.

Fundus photo of the left eye depicting subretinal mass at the posterior pole on the initial eye examination.

Figure 3B

Fundus photo of the left eye showing the marked increase in size of the subretinal mass 5 days later

Fundus photo of the left eye showing the marked increase in size of the subretinal mass 5 days later

Figure 4A

Early phase of indocyanine green angiography composite picture obtained by Heidelberg SLO

Early phase of indocyanine green angiography composite picture obtained by Heidelberg SLO

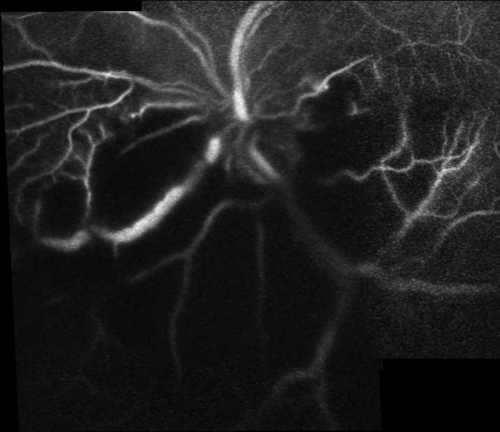

Figure 4B

Early venous phase of fluorescein angiography composite picture obtained by Heidelberg SLO

Early venous phase of fluorescein angiography composite picture obtained by Heidelberg SLO

Syphilis

Tuberculosis

Bartonella-Henselae

Cytomegalovirus retinitis

Necrotising herpetic vascular occlusions

Toxoplasmosis

Candida

Aspergillus

Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis accounts for 2 to 8% of all cases of endophthalmitis(2) . A severe manifestation of bacterial endogenous endophthalmitis is the formation of subretinal abscess which occur primarily in the immunocompromised individual(3).

Subretinal abscess is characterised by a solitary, yellowish-white, circumscribed mass-like subretinal lesion associated with overlying retinal hemorrhages and mild to moderate cellular vitreous reaction. Subretinal pseudohypopyon and exudative retinal detachment may also occur in advanced cases.

No characteristic fluorescein and indocyanine green angiographic features of subretinal abscess were defined in previously reported cases most likely due to poor general health of affected patients(3-8). We angiographically demonstrated a significant masking effect of subretinal abscess over choroidal vasculature which was even more dramatic in indocyanine green angiography. Late fluorescein staining of major retinal vessels was another fluorescein angiographic feature.

Microbiological detection of causative organism can be either done by culture of vitrectomy specimen or by cultures obtained from other affected sites. We could not detect the causative organism as the patient denied any ocular intervention. However, reported causative bacteriae include nocardia asteroides, gram-negative rods and streptococcus pneumoniae. Particularly, nocardia tends to grow along Bruch's membrane and may have an affinity for the retina pigment epithelium suggesting they spread via the choroidal rather than the retinal circulation and extend accross Bruch's membrane to produce subretinal pigment epithelial and subretinal abscess(5).

Webber et al (4) reported a 23-year-old male with a unilateral subretinal abscess who had undergone bilateral sequential lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis. Pars plana vitrectomy was performed with drainage of subretinal abscess via two retinotomies. Drained fluid was demonstrated to contain gram-negative rods identified as pseudomonas aeroginosa. One month later, the patient developed retinal detachment and proliferative vitreoretinopathy. This was repaired by lensectomy, encirclement, epiretinal membrane dissection and silicone oil fill with a subsequent visual acuity of hand movements.

Jolly et al (5) described a woman with subretinal abscess who received renal transplant and thus immuno-suppressive therapy. She had multiple concomittant brain abscesses and a cavitating lung lesion. A biopsy of the lung revealed nocardia. No ocular intervention was performed.

Rimpel et al (4) reported a man undergoing chemotherapy for multiple myeloma. He had bacterial endocarditis, multiple septic brain emboli and unilateral subretinal abscess. Postmortem evisceration material revealed gram-positive cocci in the subretinal space and inner retina.

Harris et al (3) described a 32-year-old man with beta-thalassemia with Klebsiella sepsis, liver abscess and a unilateral subretinal abscess. Despite medical intervention including vitreous tap and intravitreal antibiotics, eye lesion deteriorated. A pars plana vitrectomy was performed in which the abscess material was removed after an extensive retinectomy without any gas or oil tamponade. However, a retinal detachment occured which was successfully repaired.

Yarng et al (6) reported a 39-year-old man who had pyogenic liver abscess with bilateral endogenous Klebsiella endophthalmitis. Infection presented as a solitary subretinal abscess in his left eye. Despite repeated intravitreal antibiotics and dexamethasone injections, subretinal abscess spread and detached all of the retina.

More recently, Ng (8) et al reported another unilateral subretinal abscess in a patient with renal failure. He had concomittant brain abscess and subretinal biopsy with pars plana vitrectomy was performed. Nocardia species were noted on transmission electrone microscopy of the subretinal biopsy material. Unfortunately, one week after the initial surgery, retinal detachment was noted by ultrasound but no surgery was attempted due to the patient's risk for anesthesia.

The present case, in our opinion, should be considered immunocompromised because of high endogenous corticosteroids with organ failure. Brain Magnetic Resonance Imaging performed upon request on ophthalmologic consultation revealed a temporoparietal brain abscess and systemic broad spectrum antibiotic therapy (Ampiciline-sulbactam, cephtriaxone, ornidazole ) was started. Most reported patients described above had solitary or multiple brain abscesses while some had hepatic abscesses. Thus, every patient with subretinal abscess should be meticulously screened for other organ involvement. We suspected a Nocardia subretinal abscess and a vitreous tap, intravitreal broad spectrum antibiotic and anti-fungal injections were planned but the patient denied the treatment and sought a second opinion. He received a diagnosis of acute retinal necrosis at another institution, which we felt inappropriate. High dose acyclovir (1500 mg/m2/day) was commenced. Despite the parenteral antibiotic therapy and acyclovir therapy, exudative detachment progressed so that almost no fundus detail could be visualized but the patient did not permit any intervention.

2.Okada AA, Johnson RP, Liles WC, D'Amico DJ, Baker AS. Endogenous bacterial endophthalmitis. Report of a ten-year retrospective study. Ophthalmology 1994; 101: 832-838.

3.Harris EW, D'Amico DJ, Bhisitkul R, Priebe GP, Petersen R. Bacterial subretinal abscess: A case report and review of the literature. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 129: 778-785.

4.Webber SK, Andrews RA, Gillie RF, Cottrell DG, Agarwal K, Subretinal Pseudomonas abscess after lung transplantation. Br J Ophthalmol 1995; 79: 861.

5.Jolly SS, Brownstein S, Samad A. Endogenous Nocardia subretinal abscess. Arch Ophthalmol 1996; 114: 1147-1148.

6.Yarng SS ,Hsieh CL, Chen TL. Vitrectomy for endogenous Klebsiella pneumoniae endophthalmitis with massive subretinal abscess. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers 1997;28: 147-50.

7.Rimpel NR, Cunningham ET, Howes EL, Kim R. Viridans group Streptococcus subretinal abscess. Br J Ophthalmol 1999; 83: 373-374.

8.Ng EWN, Zimmer-Galler IE, Green WR. Endogenous Nocardia asteroides endophthalmitis. Arch Ophthalmol 2002; 120: 210-213