54 year old man with diplopia

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 1997

Volume 3, Number 20

June 11, 1997

Volume 3, Number 20

June 11, 1997

POHx: None

PMHx: "One good kidney"

Meds: None

SHx: On disability for a learning disorder since a teenager

FHx: None

Pupils: Reactive OU, No relative afferent pupillary defect

Color vision: HRR 19/20 OD 20/20 OS

External:

| OD | OS | |

| Fissure height | 7 | 5 |

| MRD | 4 | 1 |

| Levator function | 18 | 18 |

| Scleral show | 0 | 1 inferior |

| Lid crease height | 12 | 12 |

Motility: See Figure 1

Slit lamp examination: Within normal limits OU

Fundus examination: Within normal limits OU

Neurologic examination:

- Mental Status Exam: Able to remember 3/3 objects. Difficulty with spelling and math as baseline.

- Cranial Nerves: II-XII tested and intact

- Motor: 5/5 strength throughout

- Sensory: intact to temperature throughout

- Cerebellar: slightly slow rapid movements

- Gait: normal toe and heel. some difficulty with toe to heel gait.

- Deep Tendon Reflexes: 3+ throughout. toes downgoing

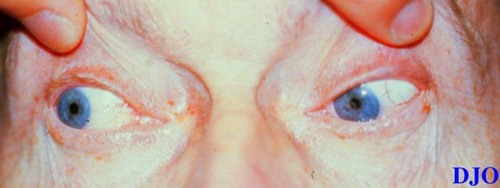

Figure 1a

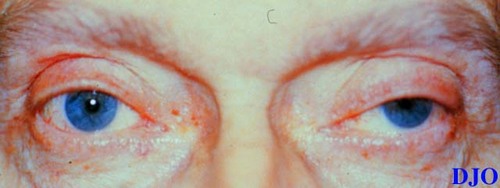

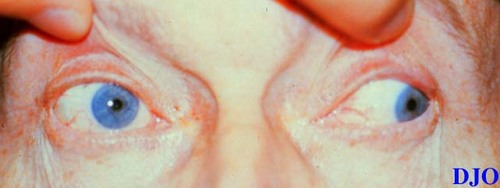

Figures 1a-1c. The above photographs demonstrate the patients attempts to look to the right, straight, and left respectively. Note the patient's ptosis OS and the limitations in motility OU. This patient also was noted to have nystagmus at extremes of lateral gaze.

Figures 1a-1c. The above photographs demonstrate the patients attempts to look to the right, straight, and left respectively. Note the patient's ptosis OS and the limitations in motility OU. This patient also was noted to have nystagmus at extremes of lateral gaze.

Figure 1b

Figure 1c

- Myasthenia

- Eaton Lambert

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Brainstem Infarct

Clinical Course:

The patient was diagnosed with a bilateral internuclear ophthalmoplegia with a motility pattern that also suggested a right CN4 and CN6 palsy. The patient also had a unilateral ptosis OS without evidence of Horner's syndrome. The initial impression was that this patient had a central nervous system ischemic event and an MRI was scheduled. After further review of the exam data, it was decided to first CHECK a tensilon test. The patient was given Tensilon 1 cc and showed no response. The patient was then given another 3 cc and within 30 seconds his ptosis and motility disturbances resolved. One to two minutes later, the ptosis and EOM limitation returned. This patient was diagnosed with probable myasthenia gravis. It was decided to still obtain the MRI to rule out any cerebral/brainstem cause for the clinical picture. The resulting study was negative.

Background:

Myasthenia gravis is a condition characterized by abnormal fatigability of the striated muscles after repetitive contraction which improves with rest. It is a disease of the myoneural junction where abnormal antibodies bind to the acetylcholine receptors.

Epidemiology:

The incidence of the condition is approximately 1 in 20,000 to 1 in 30,000. Usually it occurs in young adults (70%< 40 years of age). Older patients are usually male and are more likely to have thymoma. There can also be an infantile form which is more refractory to treatment.

Clinical Presentation:

Onset of symptoms may follow upper respiratory tract infection, stress, or pregnancy. Myasthenia often presents with ocular signs and symptoms. The most common finding is ptosis. Diplopia is also common and is frequently varys over time. Myasthenia is capable of simulating any isolated or multiple extraocular muscle palsy and may be mistaken for a supranuclear process e.g. internuclear ophthalmoplegia or gaze palsies. The hallmarks of myasthenia are variability, fatigability, and orbicularis weakness. The presence of pupil involvement or decreased vision should raise the possibility of diagnoses other than myasthenia.

Although myasthenia often begins with ocular involvement only, systemic involvement can occur. These systemic manifestations include generalized weakness in the arms and legs, difficulty swallowing, weak jaw muscles, and difficulty breathing. The systemic symptoms of myasthenia must be taken very seriously as they may herald life threatening situations.

Diagnosis:

Diagnosis of myasthenia must begin with its consideration in the differential diagnosis of any ocular motility disturbance or ptosis. Pharmacologic testing with edrophonium (Tensilon) is useful if the test is positive i.e. objective findings resolve rapidly with the administration of Tensilon. Negative Tensilon tests do not absolutely rule out myasthenia. Neostigmine may also be used in the same manner as Tensilon.

Elevated anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody titers are strongly suggestive of Myasthenia if present. However, titers will not be elevated in 10-20% of patients with systemic myasthenia and in 40-60% of patients with ocular myasthenia.

All patients with a diagnosis of myasthenia should receive a chest CT scan to rule out thymoma as this may be present in 10% of myasthenic patients. Imaging of the head should also be considered, since it is possible to have true myasthenia and intracranial pathology simultaneously.

Treatment:

Management of myasthenia should be done in conjunction with a neurologist or internist as these patients can have life threatening manifestations of their disease requiring interventions such as plasmapheresis and endotracheal intubation. If the patient's symptoms are mild observation should be considered. Acetylcholinesterases (e.g. pyridostigmine) may be used for symptomatic relief, but these agents are typically less effective for ocular symptoms. Steroids and other immunosuppressives may also be considered in patients with refractory symptoms.

2) Slamovits TL et al: Basic and Clinical Science Course Section 5 Neuroophthalmology. U.S.A., American Academy of Ophthalmology, 162-165. (1995)

3) Savino PJ, Sergott RC: Neuro-Ophthalmology. In Cullom RD , Chang Benjamin. The Wills Eye Manual Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. Philadelphia, Lippincott Company, 264-266. (1994)

4) Vaughan DG, Asbury T, Riodan-Eva P. General Ophthalmology - A Lange medical book. Connecticut, Appleton and Lange, 289-290 (1992)