48 year old man with bilateral, progressive visual loss over 20 years

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 1996

Volume 2, Number 5

October 22, 1996

Volume 2, Number 5

October 22, 1996

PMHx: Non contributory

Meds: None

SHx: Non contributory

FHx: Non contributory

Pupils: Normal OU, No APD

Motility: Full OU

Color: Normal OU

External: Normal OU

Slit lamp examination: Normal OU

Tonometry: 16 OU, ranges FROM 14-18 OU during diurnal curve measurements

Gonioscopy: Grade 4 angles, open 360 degrees without pigment, iris processes, synechiae, or bombe OU

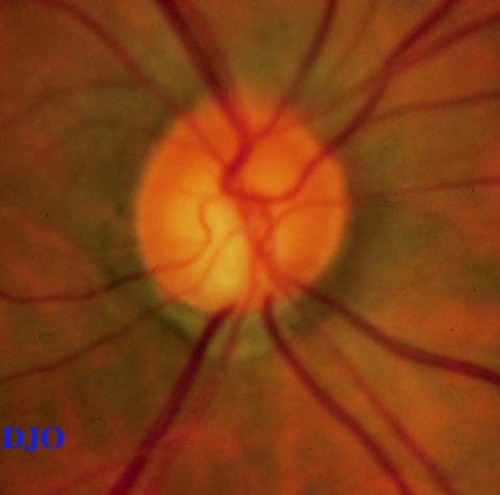

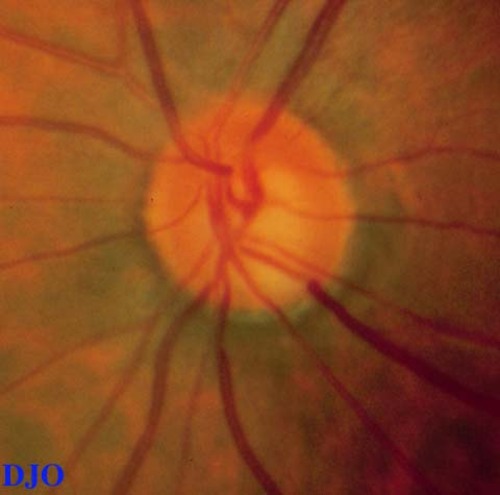

Fundus examination: Macula and vessels appeared normal, the disks are shown in Figures 1-2

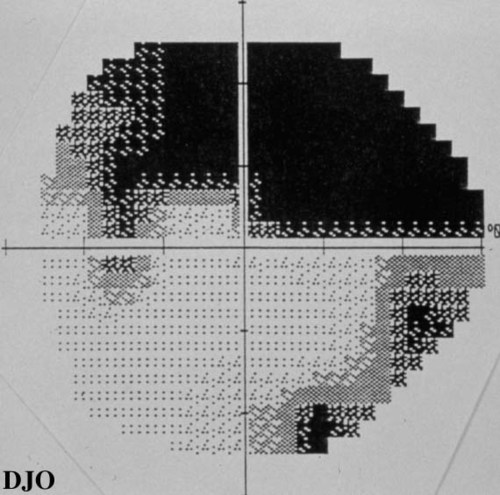

Visual fields: See Figures 3-4

Figure 1

Figures 1-2. Disks SHOW cupping and inferior temporal notching OU

Figures 1-2. Disks SHOW cupping and inferior temporal notching OU

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figures 3-4. Arcuate defects present in both visual fields.

Figures 3-4. Arcuate defects present in both visual fields.

Figure 4

- Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy

- Sectoral Optic Nerve Hypoplasia

- Hypotensive Episodes

- Past acute elevations of Intraocular Pressure FROM Uveitis, Trauma, etc.

- Compressive Intracranial Lesions

Low tension glaucoma (LTG), or normal tension glaucoma, is a progressive optic neuropathy with characteristic cupping and visual field defects. It occurs in the presence of intraocular pressures less than 21 mm Hg to the exclusion of other ocular or retinal disease. As Jay (1) wrote, this negative description is not an entirely satisfactory one. Nevertheless, LTG as defined, represents about one-sixth of all cases of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG). Prior elevations of intraocular pressure may have caused optic nerve damage, and evidence for trauma and uveitis should be sought. Carotid artery stenosis, hypotensive episodes, and ischemic optic neuropathy should also be ruled out by careful history and physical exam. MRI or CT scans need not be ordered unless there is reason to suspect a compressive lesion.

As with POAG, age and family history are important risk factors in LTG. Myopia may also be a risk factor for LTG. A mean intraocular pressure greater than 15 mm Hg may increase the likelihood of advanced visual field loss (2). Optic nerve hemorrhage, possibly FROM distortion of the lamina cribrosa and shearing of blood vessels, is found in higher frequency in patients with LTG (3), and some studies also suggest a correlation between disc damage and peripapillary crescents (4, 5).

There is controversy regarding the role of vasospasm in the pathophysiology of LTG. Corbett et al (6) first found an increased incidence of migraines among patients with LTG as compared to other POAG. Drance et al (7) have shown that digital blood flow to capillaries in the finger were decreased, with and without exposure to cold, in patients with LTG as compared with controls. However, Japanese investigators (8) have failed to confirm this. Nevertheless, many still believe that there is a link between vasospasm and LTG and have therefore explored the role of calcium channel blockers (CCB) in the treatment of LTG. Kitizawa et al (9) treated 25 patients for 6 months with nifedipine and found improvement in the visual fields of 6 patients. CCB tended to work in patients who were younger, with less severe visual field loss initially, and who had greater recovery FROM cold-induced digital vasospasm. Netland et al (10) conducted a retrospective case-controlled study which showed that patients with LTG on nifedipine for non-ocular reasons had slower progression of visual field loss. While the results are encouraging, the verdict is not in yet on the use of CCB for LTG.

2) Yamagami, J., Shirato, S., Araie, M. The Influence of the Intraocular Pressure on the Visual Field of Low-Tension Glaucoma. Acta Soc Ophthalmol Jpn 94:514 (1990)

3) Kitazawa, Y., Shirato, S., and Yamamoto, T. Optic Disc Hemorrhage in Low-Tension Glaucoma. Ophthalmology 93: 853 (1986)

4) Rockwood, E.J. and Anderson, D.R. Peripapillary Crescents and Halos in Normal-Tension Glaucoma and Ocular Hypertension. Ophthalmology 226:510 (1986)

5)Corbett, J.J., Phelps, C.D., Eslinger, P., et al. The Neurologic Evaluation of Patients with Low-Tension Glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 26:1101-1104 (1985)

6) Phelps, C.D., and Corbett, J.J. Migraine and Low-Tension Glaucoma Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 26: 1105-1108 (1985)

7) Drance, S.M., Douglas, G.R., Wijsman, K. et al. Response of Blood Flow to Warm and Cold in Normal and Low-Tension Glaucoma Patients. Am J Ophthal 105:35-39 (1988)

8) Usui, T. and Iwata, K. Finger blood flow in patients with low tension glaucoma and primary open-angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthal 76: 2-4 (1992)

9) Kitizawa, Y., Shirai, H., and Go, F.J. The effect of Ca2+-antagonist on visual field in low-tension Glaucoma. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 227:408 (1989)

10) Netland, P.A., Chaturvedi, N., and Dreyer, E.B. Calcium Channel Blockers in the Management of Low-tension and Open-angle Glaucoma. Am J Ophthalm 115:v608-613 (1993)