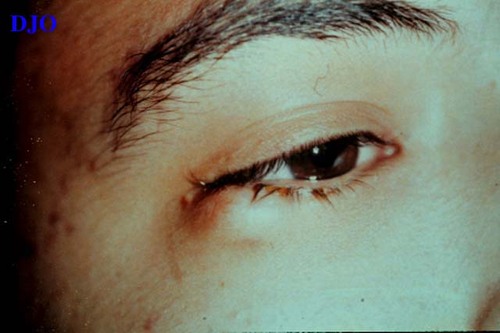

18 year old man with decrease in vision OD after being struck with a tree branch

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 1998

Volume 4, Number 24

November 2, 1998

Volume 4, Number 24

November 2, 1998

POHx: negative

PMHx: asthma

Meds: Ventolin inhaler

SHx: Non-contributory

FHx: Non-contributory

Confrontational visual fields: full

External exam: No proptosis Right upper lid ptosis and mild edema 3 mm linear laceration over the medial canthus OD Decreased sensation in V1 distribution on the right

Pupils: 3 --> 2 OD 4 --> 3 OS

Motility: Full OS

Slit lamp examination: Conjunctiva- white/quite/ no chemosis OU Cornea- clear/quiet OU Anterior chamber- deep/quiet OU Iris- normal, round pupil OU Lens- clear OU

Tonometry: OD 22, OS 21

Fundi: Disc margins sharp OU, normal macula, vessels and disc OU

Figure 1

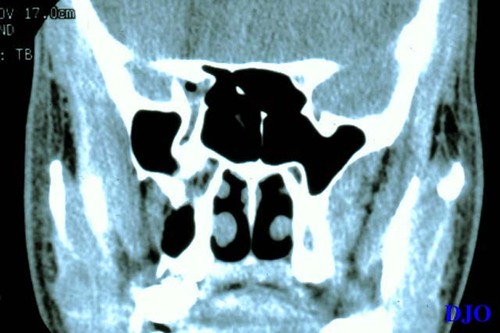

Figures 1-2. Axial and coronal CT slices through the orbits SHOW a linear hypodense area extending through the right superior orbital fissure.

Figures 1-2. Axial and coronal CT slices through the orbits SHOW a linear hypodense area extending through the right superior orbital fissure.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Quantitative CT. The three circles depict the relative densities (Hounsfield units) of the circumscribed areas. This showed the area in question (area 2) was denser than air (area 3, within the ethmoid sinus) and less dense than orbital tissue (area 1, extraocular muscle). This helped identify the hypodense area as an intraorbital foreign body and not air.

Quantitative CT. The three circles depict the relative densities (Hounsfield units) of the circumscribed areas. This showed the area in question (area 2) was denser than air (area 3, within the ethmoid sinus) and less dense than orbital tissue (area 1, extraocular muscle). This helped identify the hypodense area as an intraorbital foreign body and not air.

Figure 4

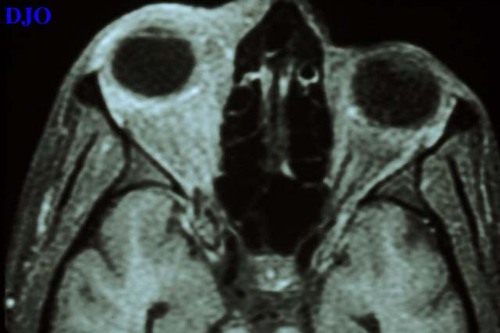

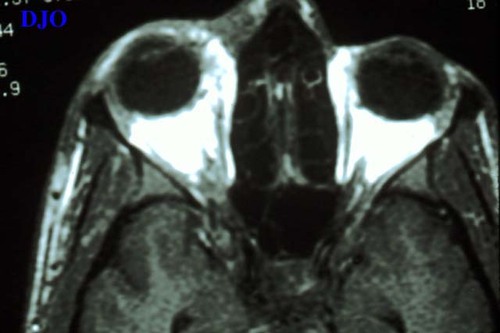

Figures 4-5. Axial MRI sections confirm the area in question to be consistent with a retained intraorbital foreign body instead of tracking emphysema.

Figures 4-5. Axial MRI sections confirm the area in question to be consistent with a retained intraorbital foreign body instead of tracking emphysema.

Figure 5

- Traumatic optic neuropathy

- Intraorbital emphysema

- Intraorbital foreign body

Clinical course: With the diagnosis of retained intraorbital foreign body consistent with vegetative material and a traumatic optic neuropathy, the patient was admitted for IV antibiotics and steroids (Flagyl, gentamycin, nafcillin and Solu-Medrol). The patient was evaluated by a number of services: neurosurgery, neuro-ophthalmology, oculoplastics and infectious disease. The options were discussed with the patient and he elected to be followed closely and consider surgical exploration if he showed signs of infection. The patient was given four days of IV antibiotics and steroids, and then discharged on oral antibiotics and a steroid taper.

At the patient's one week follow up visit, his exam was basically unchanged. His vision OD was count fingers. He had no evidence of infection. His labs were normal (WBC=6.9). A repeat CT showed the linear translucent lesion in the right superior orbital fissure as before. Again, surgical exploration was considered. However, due to the difficulty of removing the object and the risk of visual loss, it was again elected to follow the patient.

The patient was tapered off the steroids by 12 days after the accident. He continued antibiotics until 3 weeks after discharge. It is currently one year after the accident and he still declines surgical exploration of the orbit. He has showed no signs of infection and his vision is count fingers OD.

This case illustrates the difficulty in dealing with intraocular foreign bodies. Although this case has not required surgical exploration and removal of the foreign body, he may eventually develop secondary complications that require surgery. The next case presented is an example of a similar case that eventually required surgery.

A related case:

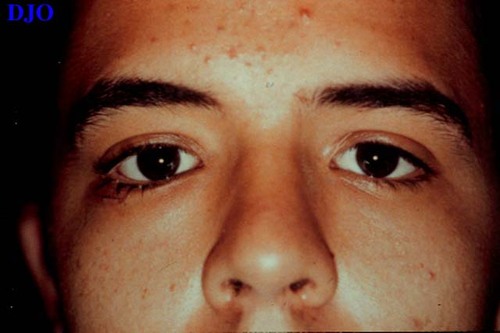

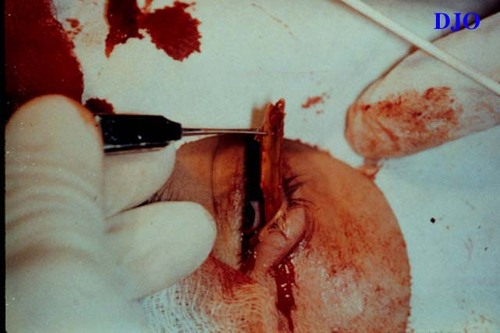

A 20-year-old Hispanic male presented with diplopia and pain in the right lower lid one year after an accident. The patient reports that he had been chased through the woods at night and ran INTO a tree. He had been admitted and treated for orbital cellulitis at that time. For the past year, he reported diplopia in upgaze. Over three weeks prior to presentation, he reported discharge OD. Two days prior to presentation, a sharp palpable mass was noted in the lateral aspect of the right lower lid. Vision was 20/30 OD, 20/25 OS.

The patient elected to undergo surgical exploration for removal of the foreign body. An initial incision was made over the palpable right lower lid mass. However, the foreign body remained attached to the area. A larger incision at the inferior fornix was made to free the mass. Surgical exploration revealed 6 fragments of wood that were removed through the inferior fornix. The patient noted immediate improvement of the diplopia after the surgery.

These two cases illustrate the difficulty in identifying and treating organic intraorbital foreign bodies. Initially it is critical to accurately identify the foreign body. On radiographic studies, it is possible to misdiagnosis wooden foreign bodies as intraorbital emphysema- a condition which does not require intervention. The shape of these foreign bodies (typically, linear) and their location (anywhere within the orbit), help distinguish these wooden foreign bodies FROM orbital emphysema, which typically assumes a more rounded shape is located more superiorly in the orbit. Furthermore, multiple foci of hypodensity (i.e. Case 2) should heighten the concern of a possible retained wooden foreign bodies. Serial CT's will demonstrate absorption of intraorbital air, while a vegetative foreign body will likely have a more stable appearance. Quantitative CT, as demonstrated in case #1 (fig 3) should be used to eliminate some of the radiographic uncertainty. Others have advocated the use of MRI to better define retained vegetative foreign bodies. Once identified, there is controversy regarding the management of such cases. The central question that must be answered in each case, is whether the risk of retention of the foreign body (infection) is greater than the risk of surgical exploration (blindness, dislodging, but not removing the foreign body, and cavernous sinus injury). In addition, a patient with foreign bodies penetrating in the region of the superior orbital fissure/ cavernous sinus should monitored for post-traumatic carotid-cavernous sinus fistula. In most cases the foreign body is relatively easy to access without causing surgical complications. However in the first case we presented, the foreign body is not easily removed FROM the superior orbital fissure. If surgery were pursued a transcranial approach, and its associated risks, would be necessary. In the literature, there are those who advocate immediate exploration and removal of any foreign body.[1, 2] In contrast, there are those who recommend a more conservative approach with foreign matter lying deep within the orbit[3][4] or within the cranium[5]. To the infectious disease purist, conservative therapy may seem alarming, but it may offer the best compromise. Unfortunately, we are unaware of any reports that more quantitatively predict the infectious risk given the nature of the wooden foreign body (i.e., live, processed, dormant). If a vegetative foreign body is managed without surgery, it is imperative that such patients are closely monitored for potential complications, especially fungal infections, which may present very insidiously.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

2) Sullivan, T.J., et al., Anaerobic orbital abscess secondary to intraorbital wood. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol, 1993. 21(1): p. 49-52.

3) Woolfson, J.M. and R.E. Wesley, Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomographic scanning of fresh (green) wood foreign bodies in dog orbits. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg, 1990. 6(4): p. 237-40.

4) Macrae, J.A., Diagnosis and management of a wooden orbital foreign body: case report. Br J Ophthalmol, 1979. 63(12): p. 848-51.

5) Chaudhri, K.A., et al., Penetrating craniocerebral shrapnel injuries during "Operation Desert Storm": early results of a conservative surgical treatment. Acta Neurochir, 1994. 126(2-4): p. 120-3.