49 year old man with 6 months of swelling around the right eye

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 1998

Volume 4, Number 20

July 6, 1998

Volume 4, Number 20

July 6, 1998

PMHx: None

PSHx: Appendectomy

Meds: As above

Allergies: None

SHx: Non contributory

FHx: None

External: 2 mm of proptosis OD with Hertels

Pupils: Equal, briskly reactive to light. No RAPD

Extraocular Movements: Normal OU

Slit lamp examination OD: 2+ conjunctival injection, cornea clear, Anterior chamber shallow, with trace white blood cells, the iris showed 2 patent peripheral iridectomies.

Slit lamp examination OS: Normal with deep anterior chamber

Gonioscopy: Shallow OD, but open angle. OS angle is wide open

Intraocular pressure: 20 OD, 14 OS

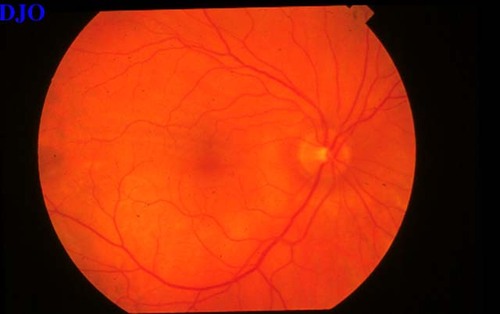

Fundus examination: OD see below, Normal OS

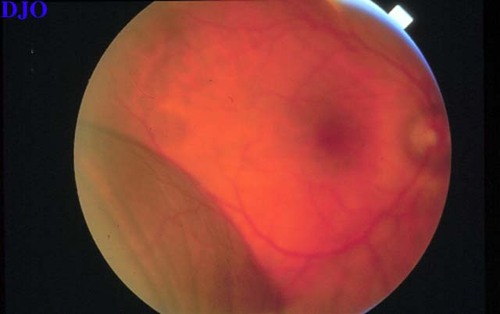

Figure 1

Anterior segment examination showing a diffusely injected conjunctiva. The cornea was clear, the anterior chamber shallow with 1+ white blood cells.

Anterior segment examination showing a diffusely injected conjunctiva. The cornea was clear, the anterior chamber shallow with 1+ white blood cells.

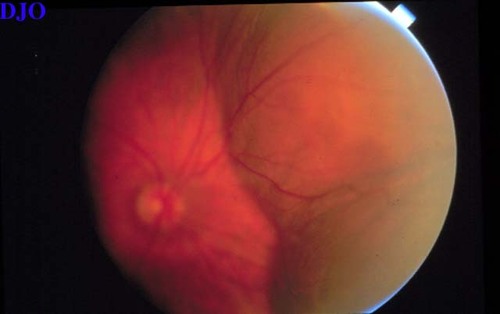

Figure 2

Figures 2-3. Fundoscopic examination of the right eye revealing an elevated mass in the inferotemporal quadrant and the nasal half of the retina. There was no retinal detachment or vitritis. The fluid did not shift with position change. Examination of the far periphery showed 360 degree cilio-choroidal detachment in an annular configuration.

Figures 2-3. Fundoscopic examination of the right eye revealing an elevated mass in the inferotemporal quadrant and the nasal half of the retina. There was no retinal detachment or vitritis. The fluid did not shift with position change. Examination of the far periphery showed 360 degree cilio-choroidal detachment in an annular configuration.

Figure 3

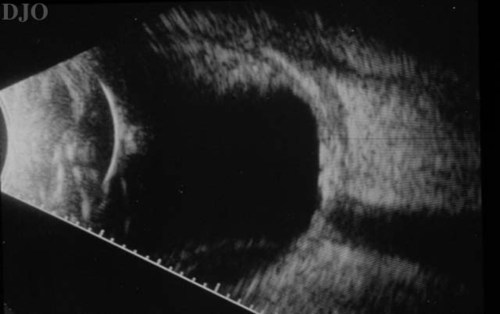

Figure 4

B-scan ultrasonography of the right eye showing a thickened sclera with an overlying choroidal detachment. Note the abrupt elevation of the choroidal detachment. This, along with the thickness of the membrane, differentiates it FROM a retinal detachment.

B-scan ultrasonography of the right eye showing a thickened sclera with an overlying choroidal detachment. Note the abrupt elevation of the choroidal detachment. This, along with the thickness of the membrane, differentiates it FROM a retinal detachment.

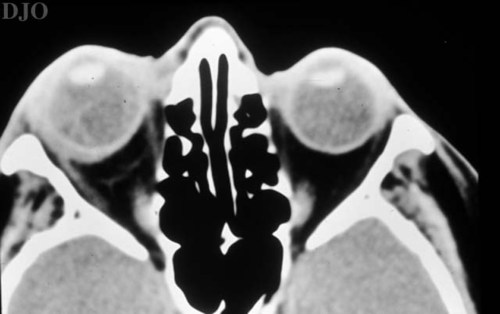

Figure 5

CT scan of orbits without contrast demonstrating a thickened sclera and evident choroidal detachments.

CT scan of orbits without contrast demonstrating a thickened sclera and evident choroidal detachments.

Anterior and Posterior Scleritis

Usually presents with pain and redness that often awakens the patient FROM sleep. The conjunctival, episcleral, and scleral vessels are inflamed, leading to a bluish discoloration of the sclera. Scleritis is more common in women and is often unilateral. Work-up is routinely negative in the unilateral cases. B-scan ultrasonography shows diffuse thickening of the choroid, sclera, and episcleral tissues. Classically, the T-sign is present in cases of posterior scleritis. The T-sign is created by the fluid beneath Tenon's capsule that creates a squaring off of the interface between the optic nerve and the sclera. Fluoroscein angiography may SHOW punctate areas of leakage. The choroidal detachment is felt to be a result of the congested sclera. This congestion increases resistance to flow in the vortex veins and through the intact sclera, leading to choroidal effusions.

Uveal Effusion Syndrome

Bilateral choroidal effusions in males. Can present with injected episcleral vessels but has minimal associated pain. Fundus examination reveals multiple foci of hyperpigmentation at the level of the RPE ("leopard skin" spots). B-scan ultrasonography reveals diffuse choroidal thickening. Poor response to corticosteroids. The choroidal detachment is secondary to an anatomical abnormality in the sclera, leading to increased resistance to flow in the vortex veins.

Rhegmatogenous Retinal Detachment

On clinical examination, the presence of a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is usually obvious.

Post-operative

Easily ruled out by clinical history.

Malignancy

Malignancies presenting as choroidal detachment include malignant melanoma, metastatic, and lymphoproliferative disorders. The presentation is usually without pain (unless necrotic), and various clinical findings help in the diagnosis. The presence of sentinel vessels on the conjunctiva can localize an intraocular tumor. Decreased transillumination is usually found in intraocular tumors, whereas choroidal effusions can demonstrate increased transillumination (Hagen's sign). B-scan ultrasonography will aid in the diagnosis, revealing an intraocular mass.

Vascular Etiology

Vascular causes include carotid-cavernous fistula and dural-sinus fistula. These vascular communications cause reversal of flow in the episcleral venous plexus, thus obstructing drainage FROM the suprachoroidal space. Clinical clues to fistulas are dilated, and often "arterialized" conjunctival vessels, elevated intraocular pressure, and dilated retinal veins. Historical clues include a history of head trauma, pulsatile tinnitus, and abrupt onset.

This case represents an atypical cause of a narrow anterior chamber angle and elevated intraocular pressure. Unilateral narrow angle should raise questions as to secondary causes of shallowing the anterior chamber. The possibilities include annular ciliochoroidal detachment, phakomorphogenic, and a posterior intraocular mass.

Annular ciliochoroidal detachment causing secondary angle closure is well documented. The detachment creates an anterior rotation of the ciliary body on the scleral spur. The resultant angle closure leads to an elevated intraocular pressure. Annular ciliochoroidal detachments are caused by posterior scleritis, ciliary body ring melanoma, intraocular surgery, and Uveal Effusion Syndrome. Ultrasonography, both B-scan and UBM, are crucial in identifying the cause.

The differential diagnosis of choroidal detachment is extensive. There are iatrogenic causes (medications-HCTZ/triamterene, post operative, PRP, RD repair), inflammatory causes (Scleritis, orbital pseudotumor, VKH, Wegener's, etc.), vascular causes (C-C fistula, dural-sinus fistula, eclampsia, Valsalva), malignant causes (metastasis, leukemia, multiple myeloma), and anatomical causes (nanophthalmos, Uveal effusion syndrome). The clinical history will often lead to the diagnosis. If the etiology is unclear, ancillary testing is warranted.

On ultrasonography, the classic finding in choroidal detachment is the abrupt elevation of the detached choroid. The choroidal signal is thicker than that of detached retina and the choroidal detachment will not undulate with eye movements as a rhegmatogenous retinal detachment would.

The reported case shows a classic choroidal detachment. (Figure) Ultrasonography also revealed a thickened sclera with fluid in sub-Tenon's space. These findings are characteristic of posterior scleritis. Ultrasound is the preferred diagnostic modality for posterior scleritis. The CT scan, which some feel is as effective as ultrasound in diagnosis, showed thickened sclera and a prominent choroidal detachment.

Posterior scleritis is a disease that can present with an isolated choroidal mass, choroidal effusion, choroidal folds, cystoid macular edema, and exudative macular detachment in a patient with ocular pain. It can be bilateral and affects women more often than men. The most common cause is Rheumatoid arthritis, which accounts for nearly 30% of cases. Less common causes include Wegener's granulomatosis, orbital inflammatory pseudotumor, VKH, and sympathetic ophthalmia. The diagnosis of posterior scleritis is often delayed due to its nonspecific presentation. Non-steroidal anti- inflammatory agents have been used to successfully treat posterior scleritis, however, traditionally, steroids are needed. Both periocular and systemic steroids have been reported to be effective. A work-up is indicated in those cases that are bilateral.

KEY POINTS:

- Always perform goinioscopy on both eyes in the setting of angle closure.

- If the clinical picture does not concur with the presumed diagnosis, one must rethink the diagnosis.

- Annular ciliochoroidal detachments can cause secondary angle closure due to anterior rotation of the ciliary body on the scleral spur.

Figure 6

Two weeks post-treatment with naproxen. The choroidal detachments have nearly resolved. Subtle choroidal folds are noted superior to the fovea

Two weeks post-treatment with naproxen. The choroidal detachments have nearly resolved. Subtle choroidal folds are noted superior to the fovea

2) Chaques VJ, Lam S, Tessler HH, Mafee M. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of posterior scleritis. Ann Ophth 25:89-94. (1993)

3) Fekrat S, Green WR. Ciliochoroidal effusion. In: Tasman W, Jaeger EA, eds. Duane's Clinical Ophthalmology, revised ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, v. 4, chap. 52. (1996)