62 year old female with blurry vision

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 2001

Volume 7, Number 7

November 1, 2001

Volume 7, Number 7

November 1, 2001

Previous ocular history: None

Past Medical History:

- Hypertension

- Hyperthyroidism

- Chronic Bronchitis

- Gastritis

Medications: Dyazide; Atenolol; Prilosec; Estrace;Synthroid

Family and Social History: Non-contributory.

Pupils: Normal (OU), no APD

Motility: Full (OU)

Tonometry: Normal (OU)

Slit Lamp Examination: Normal (OU)

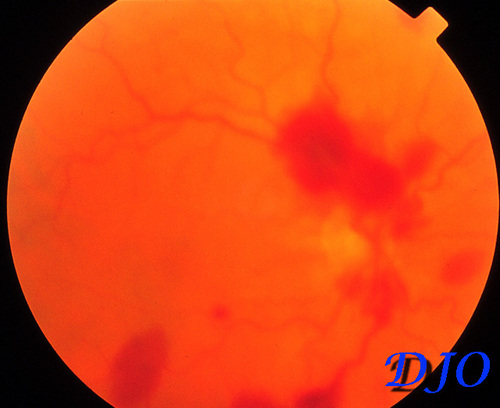

Fundus Examination:

Figure 1

Right Eye. Multiple peripapillary intraretinal and sub-ILM hemorrhages are observed along with mild vascular tortuosity

Right Eye. Multiple peripapillary intraretinal and sub-ILM hemorrhages are observed along with mild vascular tortuosity

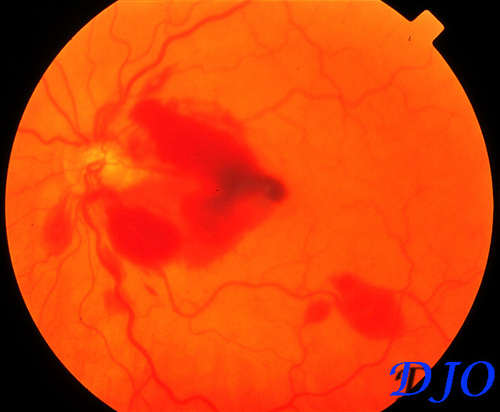

Figure 2

Left Eye. Multiple peripapillary intraretinal hemorrhages are present including a larger intraretinal hemorrhage extending INTO the macula with a small foveal sub-ILM component. Mild vascular tortuosity is also observed.

Left Eye. Multiple peripapillary intraretinal hemorrhages are present including a larger intraretinal hemorrhage extending INTO the macula with a small foveal sub-ILM component. Mild vascular tortuosity is also observed.

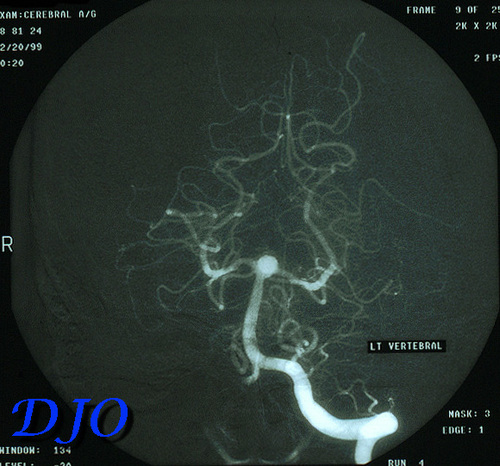

Figure 3

Cerebral angiogram with selective injection of the left vertebral artery revealing an aneurysm at the tip of the basilar artery upon presentation.

Cerebral angiogram with selective injection of the left vertebral artery revealing an aneurysm at the tip of the basilar artery upon presentation.

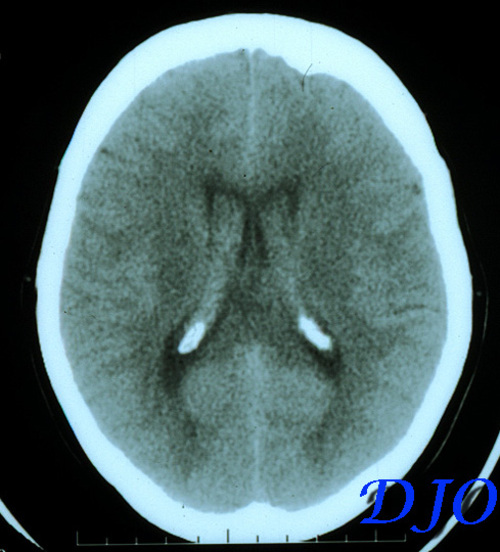

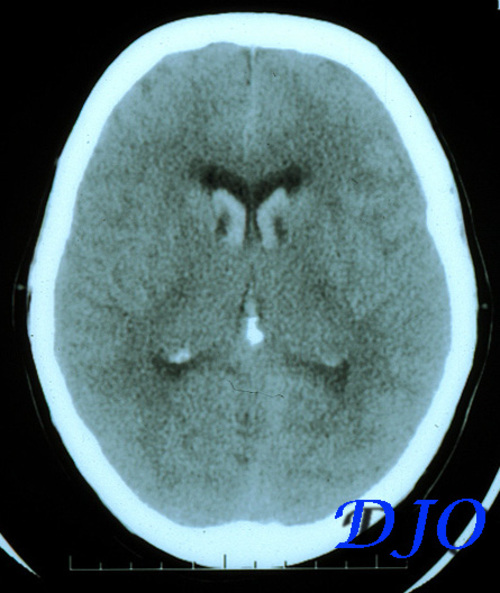

Figure 4

Presurgical contrast CT revealing hemorrhage in the lateral ventricles.

Presurgical contrast CT revealing hemorrhage in the lateral ventricles.

Figure 5

Presurgical contrast CT revealing widespread intraventricular hemorrhage.

Presurgical contrast CT revealing widespread intraventricular hemorrhage.

- Anemic Retinopathy

- Terson’s Syndrome

- Valsalva retinopathy

- Purtscher’s retinopathy

- Shaken Baby Syndrome

The association of vitreous and subarachnoid hemorrhage was originally described by Litten (1) in 1881 and subsequently by Terson in 1900 (2). Accordingly, Terson’s syndrome describes the presence of vitreous hemorrhage with any form of intracranial or subarachnoid hemorrhage, commonly secondary to aneurysmal rupture. It is most often reported with aneurysms of the anterior circulation, particularly those of the anterior communicating artery.

Approximately 20% of patients with spontaneous or posttraumatic subarachnoid hemorrhages present with intraocular hemorrhage (3). Due to the underlying morbidity in these patients, many do not present with symptoms until days to weeks after surgery or after the hemorrhagic event. Visual impairment is usually bilateral and often severe with visual acuity reduced to hand motion or light perception in many cases. The hemorrhages are typically confined to the peripapillary and macular areas and commonly found between the internal limiting membrane (ILM) and the superficial retina (3,4) although they may occur at any level. Dome-shaped accumulations of blood may appear underneath the ILM and resulting damage to its integrity may predispose to epiretinal membrane formation or surface wrinkling retinopathy via glial cell proliferation through gaps in the ILM (5). Occasionally these hemorrhages may extend INTO the vitreous. Additionally, retinal detachments have also been reported in patients with Terson’s syndrome (6,7).

The pathogenesis of Terson’s syndrome remains controversial. Terson originally proposed that intraocular hemorrhage was due to the rupture of peripapillary and epipapillary capillaries FROM retinal venous stasis secondary to a sudden increase in intracranial pressure. Specifically, it has been suggested that increased intracranial pressure produces a rapid effusion of CSF through the communication of the subarachnoid space within the optic nerve sheath. The dilated retrobulbar portion of the optic nerve then compresses and obstructs the retinochoroidal anastomoses and the central retinal vein resulting in retinal venous stasis and retinal hemorrhage (8,9).

The hemorrhages usually resolve spontaneously within six to twelve months and hence conservative management is the rule. However, pars plana vitrectomy may be indicated to facilitate visual recovery in visually immature infants and adults who present with bilateral vitreous hemorrhages that are unlikely to resolve in a reasonable period of time (10). Unfortunately, visual results may be discouraging in infants especially but in adults as well due to amblyopia or direct brain damage caused by the cerebrovascular incident (11). Nonetheless, retinal and vitreous hemorrhages are a relatively common phenomenon in patients surviving subarachnoid hemorrhages and routine funduscopic examination is essential for the prevention of visual morbidity.

2) Terson A. De l'hemorrhagie dans le corps vitre au cours de l'hemorrhagie cerebrale. Clin Ophthalmol , 1900. 6:309.

3) Shaw HE Jr; Landers MB; Sydnor CF. The significance of intraocular hemorrhages due to subarachnoid hemorrhage. Annals of Ophthalmology, 1977 Nov, 9(11):1403-5.

4) Gass JDM. Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Diseases: Diagnosis and Treatment, 3rd edition. St Louis, CV Mosby Co, 1987, 560

5) Keithahn MA; Bennett SR; Cameron D; Mieler WF. Retinal folds in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmology, 1993 Aug, 100(8):1187-90.

6) McRae M; Teasell RW; Canny C. Bilateral retinal detachments associated with Tersons syndrome. Retina, 1994, 14(5):467-9.

7) Velikay M; Datlinger P; Stolba U; Wedrich A; Binder S; Hausmann N. Retinal detachment with severe proliferative vitreoretinopathy in Terson’s syndrome. Ophthalmology, 1994 Jan,101(1):35-7.

8) Biousse V; Mendicino ME; Simon DJ; Newman NJ. The ophthalmology of intracranial vascular abnormalities. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 1998 Apr, 125(4):527-44.

9) Miller AJ, Cuttino JT. On the mechanism of massive preretinal hemorrhage following rupture of a congenital medial-defect intracranial aneurysm, Am J Ophthalmol, 1948. 31:15-24.

10) Schultz PN; Sobol WM; Weingeist TA. Long-term visual outcome in Terson syndrome. Ophthalmology, 1991 Dec, 98(12):1814-9.

11) Terson syndrome. Results of vitrectomy and the significance of vitreous hemorrhage in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 1998 Mar;105(3):472-7.