72 year old male with progressive bilateral decrease in vision

Digital Journal of Ophthalmology 2002

Volume 8, Number 4

May 1, 2002

Volume 8, Number 4

May 1, 2002

Past Ocular History: recently diagnosed with glaucoma

Past Medical History: hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, alcohol abuse, chronic pancreatitis

Medications: Alphagan, Norvasc, Zocor, Zantac

Family History: Non-contributory.

Pupils: Equal, round, and reactive to light. + afferent pupillary defect OS

Motility: Full OU

Introcular pressure: 16 mm Hg OD, 14 mmHg OS

Slit lamp exam: 1+ nuclear sclerotic cataract

Fundus exam: normal macula, vessels, periphery OU

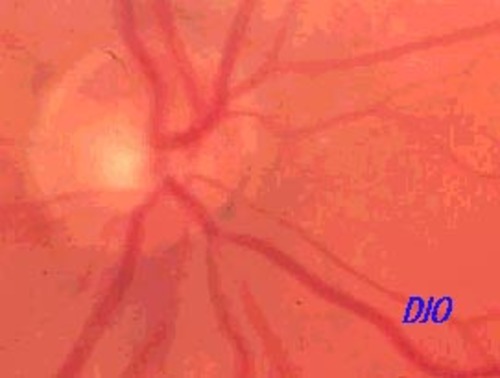

Figure 1a

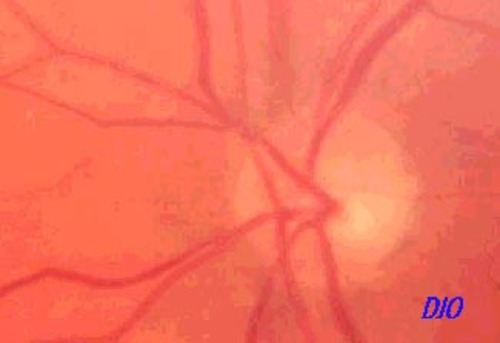

Figures 1a-1b. There is pallor of the left optic nerve.

Figures 1a-1b. There is pallor of the left optic nerve.

Figure 1b

The patient underwent a transsphenoidal resection of the pituitary mass.

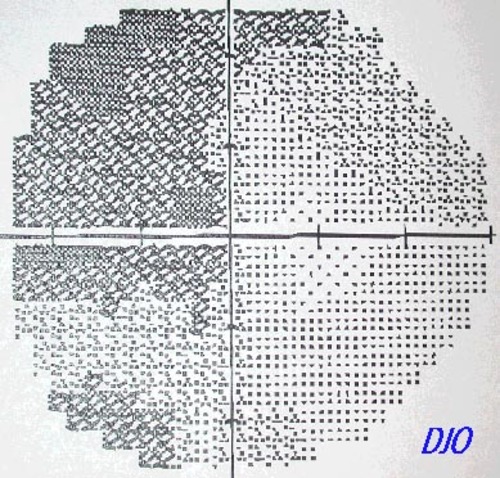

Figure 1a

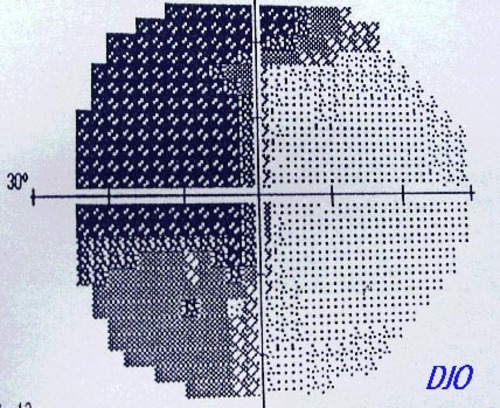

Figures 1a-1b. Humphrey visual field reveals a bitemporal hemianopia

Figures 1a-1b. Humphrey visual field reveals a bitemporal hemianopia

Figure 1b

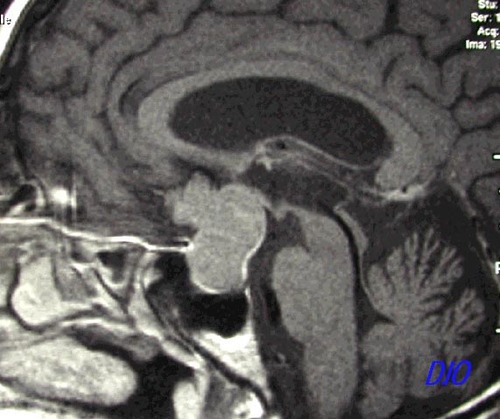

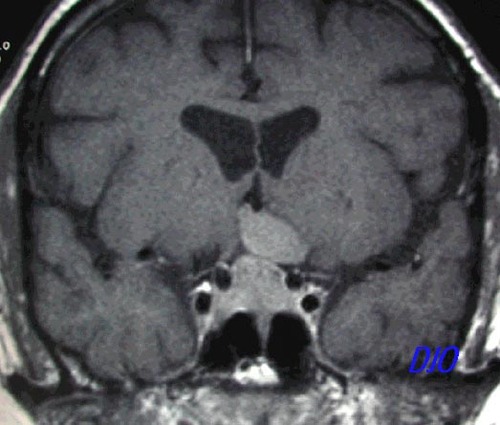

Figure 2a

Figures 2a - 2b. MRI shows a homogeneous mass extending superiorly FROM the pituitary fossa INTO the third ventricle and anterior cranial fossa.The mass extends superiorly FROM the pituitary fossa INTO the third ventricle and laterally toward the cavernous sinuses

Figures 2a - 2b. MRI shows a homogeneous mass extending superiorly FROM the pituitary fossa INTO the third ventricle and anterior cranial fossa.The mass extends superiorly FROM the pituitary fossa INTO the third ventricle and laterally toward the cavernous sinuses

Figure 2b

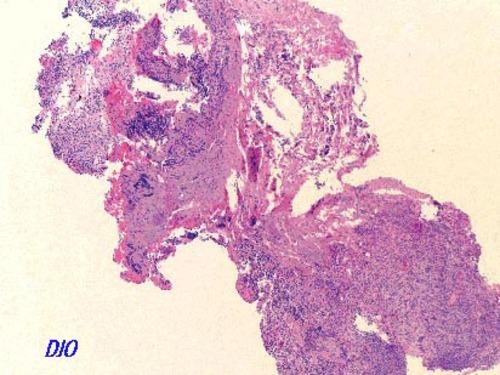

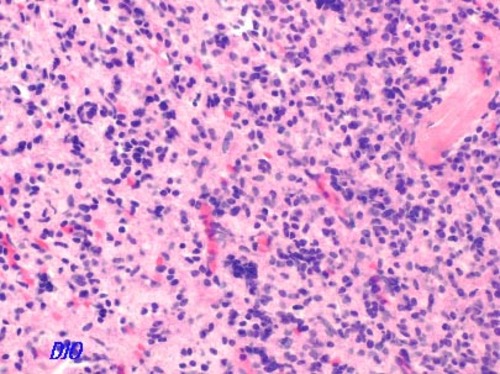

Figure 3a

Figures 3a-3b. Pathology revealed a pituitary adenoma which did not immunoreact with antibodies to ACTH, FSH, LH, TSH, prolactin, S-100 (marker for melanoma and neuroectodermal tumors), or L-26 (B-cell marker)

Figures 3a-3b. Pathology revealed a pituitary adenoma which did not immunoreact with antibodies to ACTH, FSH, LH, TSH, prolactin, S-100 (marker for melanoma and neuroectodermal tumors), or L-26 (B-cell marker)

Figure 3b

Craniopharyngioma

Meningioma

Chiasmal glioma

Pituitary apoplexy

Aneurysms

Trauma

Infection: TB, syphilis, bacterial, fungal

Sarcoid

Drugs: ethambutol

Demyelinating disorders

Pituitary tumors account for approximately 10-15% of all intracranial neoplasms. Prolactin-secreting tumors are the most common, followed by nonsecreting tumors and those that produce growth hormone, ACTH, FSH, LH, and TSH. Tumors less than 10mm in size are referred to as microadenomas and those greater than 10mm are termed macroadenomas.

Symptoms are related to the size and extent of local invasion of the tumor. Uni- or bitemporal hemianopia may occur as a result of chiasmal compression as the tumor extends superiorly FROM the sella turcica. Frontal headaches may also be a prominent clinical feature as the tumor stretches the diaphragma sellae, the dural sheath covering the superior aspect of the sella turcica. Tumors that expand INTO the cavernous sinus may cause ophthalmoplegia, sensory disturbances, and Horner's syndrome as a result of damage to cranial nerves III, IV, V, VI and sympathetic fibers. Secreting tumors typically present to the internist with endocrinologic symptoms and are often diagnosed prior to visual field loss, whereas nonsecreting tumors typically present after visual field loss and thus, are more commonly diagnosed by ophthalmologists.

A small percentage of patients with pituitary adenomas develop partial necrosis or hemorrhage of the tumor, known as pituitary apoplexy. Symptoms of rapid visual loss, ophthalmoplegia, headache, and altered mental status occur over hours as the tumor rapidly expands upward, compressing the chiasm and cavernous sinus while causing increased intracranial pressure. Management of this serious complication includes emergent neuroimaging to rule out expanding aneurysm, high-dose corticosteroids, and possible neurosurgical decompression.

Findings on exam may or may not include optic nerve atrophy (disc edema is not a characteristic finding). An afferent pupillary defect may also be present if there is asymmetric compression of optic nerve axons. Formal visual field testing characteristically shows a uni- or bi-temporal hemianopia. In the initial stages, there is usually a greater loss of the superior aspect of the visual field due to greater compression of the inferior part of the optic chiasm. CT findings include relatively iso- or hyperdense lesions that enhance homogeneously with contrast.

Management of pituitary tumors is dependent upon the size and secretory nature of the tumor. Options include medical management with hormone-suppressing agents, surgery, and irradiation. Up to 80% of prolactin-secreting microadenomas are successfully treated with bromocriptine, a dopamine agonist that inhibits prolactin secretion and serves to reduce the size of the tumor. Macroadenomas or tumors not responsive to medical management are removed surgically, most commonly via the transsphenoidal route, with adjunctive radiation therapy. Complications of surgery and radiation are pituitary insufficiency, optic neuropathy, and seizures.

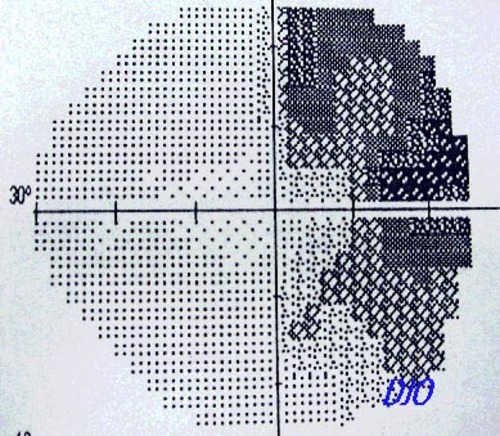

The visual prognosis after surgical excision is favorable. A series of 59 patients who underwent transsphenoidal surgery revealed that 90% had improved visual acuity and visual fields, while 63% experienced a full recovery2. Another series showed that improvement is often dramatic in the first week after surgery, but may continue to slowly improve up to 3 years after excision3. Size of the tumor and extent of chiasmal compression are other variables that may affect the visual prognosis in these patients.

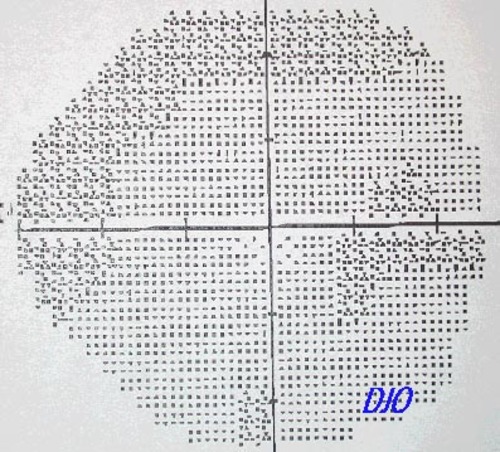

Figure 4a

Figures 4a-4b. Post-operative Humphrey visual fields.

Figures 4a-4b. Post-operative Humphrey visual fields.

Figure 4b

Ciric et al.: Transsphenoidal microsurgery of pituitary

macroadenomas with long-term follow-up results. J Neurosurg 59:395-401, 1983.

Kerrison et al., Stages of improvement in visual fields after pituitary tumor resection. AJO 130:813-820, 2000.